Sándor Hornyik

Post-communist iconology

If one thinks of Cesare Ripa or Nicolas Poussin, then perhaps it is not so difficult to see that the first iconologists were in fact artists whose work, deeply embedded in society and culture, inspired the first iconographists. However, in the name of scientific purposes, fuelled by the modern cult of positivism and rationalism, Erwin Panofsky and his followers sought to separate images from the personal desires and motivations of their creators. Thus, according to many, iconology has become a mere tool of mapping, an illustration of the history of ideas, and the special potential, power and energy of images has been overshadowed. Then, in the last third of the 20th century, along with the postmodern critique of modernity, German, French, and American art historians rediscovered the specific (intellectual and emotional) logic of images from the perspective of social history and post-structuralism, which, as a kind of special psychohistory, reveals the unprecedented complexity of history and culture.

A renitent iconologist and an enthusiastic reader of Nietzsche, Aby Warburg referred to images, even in the modern era of rationalism, as “canned energy that stores emotional and intellectual energies, desires, and motivations” whose power has always been recognized (albeit more on an emotional than an intellectual level) by politicians and merchants as by artists and designers. The postmodern followers of Warburg and Panofsky thus expanded the iconological arch spanning from the Renaissance and Counter-Reformation to technical images and the World Wars for the era of the Cold War and global capitalism, when such reflected artists as Robert Rauschenberg and Jean-Luc Godard continued to shape our knowledge of how images operate. The second half of the twentieth century, however, did not enter history as the heyday of avant-garde, but of late capitalism, when, despite the critical intentions of avant-garde art, its subversive creativity and innovativeness was integrated into the technologies of creating the capitalist and socialist spectacle, an ideologically organized imaginary worldview. Of course, the avant-garde itself reacted to the consciousness-shaping power of capitalist economy and politics by pointing out the cultural logic of recuperation in the footsteps of Roland Barthes and Guy Debord, and responded to the challenges with various programs of hijacking and appropriating popular images. Cubist collage and Dadaist photomontage, for example, were absorbed into consumer culture as quickly as the biomorphic shapes of surrealism, to which situationists and pop art responded by re-interpreting images of mass culture and daily politics (the former called this technique détournement, the latter appropriation).

The post-communist reinterpretation of communist iconography began in Hungary as early as the 1970s, with internationally well-known pieces (actions and photographs) by Dóra Maurer, Sándor Pinczehelyi and Bálint Szombathy. In the eighties, the process accelerated even further in the post-modern wave of New Wave, which had actually already crushed the original cultural context and pathos of communist icons. Later, the slow extinction of the socialist system made some elements of old communist iconography obsolete and even kitschy. However, the deeper interpretation of allegorical figures and symbolic forms, the visual processing of the past, the analysis of the optical unconscious of visual culture with a social-historical, anthropological or psychohistorical motivation, were not realized due to lack of interest, time and money. The real and (in the Derridean sense) imaginary ghosts of communism thus continued to permeate not only macroeconomics but also the personal dimensions of micro-history, because they could easily change shape and form. Perhaps this absence, or the paradoxically haunting situation (the past lived on, but in a different form) also motivated artists to breathe new life into communist iconography from the late nineties.

As one of the earliest exploitations of the memory confused by the change of regime, painter Attila Szűcs (an artist rooted in post-conceptualism) painted a picture of the number one icon of socialism, the chief of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party, János Kádár, who passed away not long before the regime change in 1989, in a manner that it also recalled the heyday of propagandistic Hungarian television of the seventies.

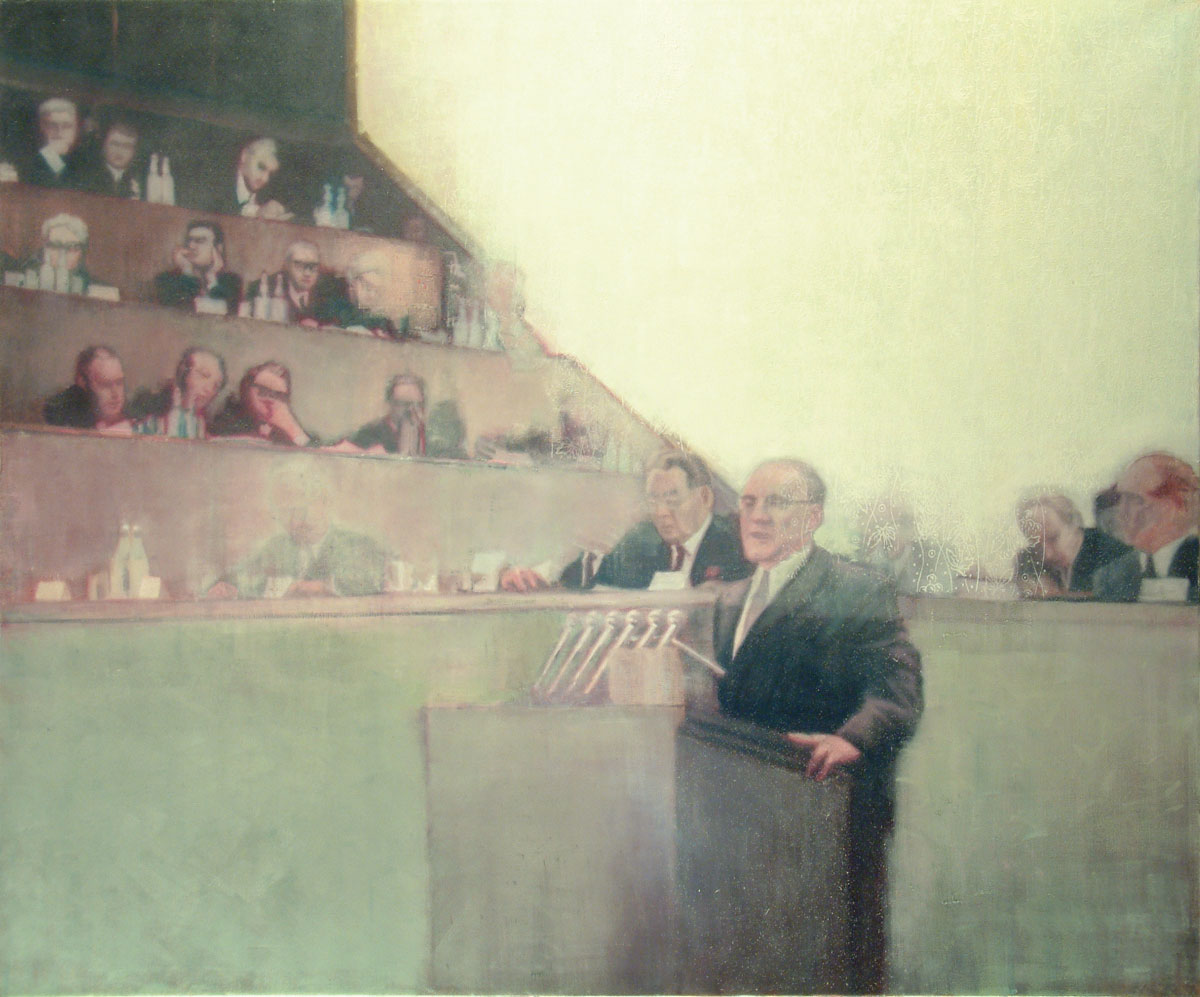

However, not only the propaganda and the politically controlled media, as well as the figures of Brezhnev and Kádár, but memory itself and memory politics came into focus on the picture entitled Congress (2002). In a blurry painting reminiscent of a flickering TV screen, the characteristic wall patterns (painted with a roller) of the sixties and seventies also recreate the sleepy, worn-out mood of the era, and at the same time refers to the way in which mediated reality has transformed the tangible world of people’s lives. In other words, the picture casts an eerie light on how János Kádár, the bloodthirsty retaliator of the 1956 revolution, became the protector of Hungarians, and who, according to some legends, even stood up to the Soviet Union when it came to the well-being and the living standard of the Hungarian people.

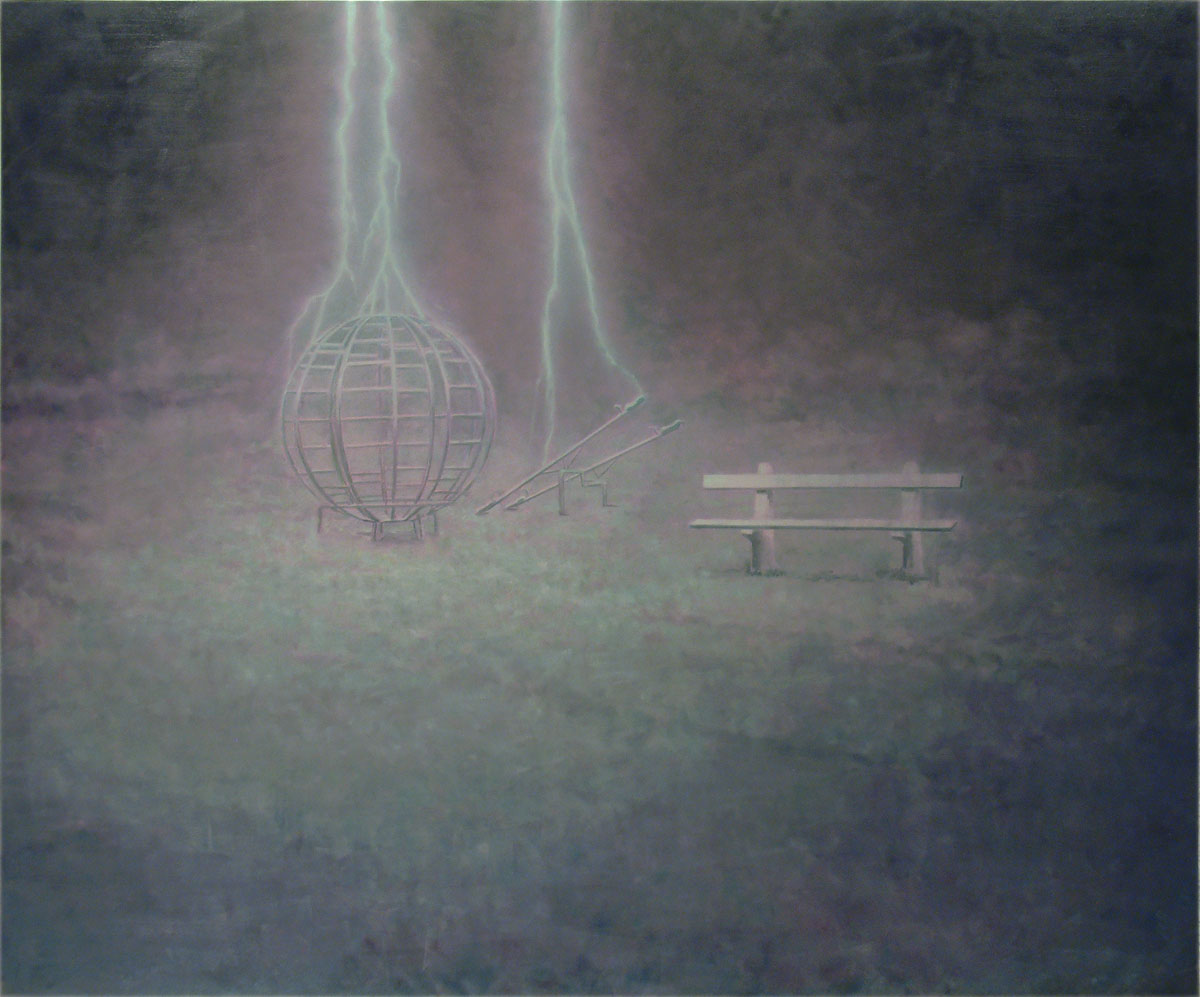

As old socialist interiors faded away and gave way to something else, and as Kádár’s legend became the subject of cult history analysis, the concept of memory and remembrance has also been transformed by the beginning of the 21st century: thanks to the information technology and critical “revolutions”, they have become the focus of scientific interest in fields ranging from historiography to psychology and neuroscience to the study of artificial intelligence. Post-communist nostalgia, now presented in this harsh way and new spirit, has appeared before on Szűcs’s earlier paintings from the nineties. They featured a special lieu de memoire, the socialist-era playground, which was not at all a prominent location in communist iconography, but the rotten red benches and rusty rocket- and globe-shaped climbers beautifully reflected the sad afterlife of communist utopias.

Szűcs became an artist in the intermediary, critical mentality of the nineties, thus experimenting with the self-reflexive and painterly critique of painting as a program, therein which he relied on the visuality of a blind spot that simultaneously produced formalist (abstract art) and abstract (epistemological) associations. So he painted blurry patches on his abstract and figurative paintings (depicting, for example, playgrounds or holiday resorts) that obscured part of the subject.

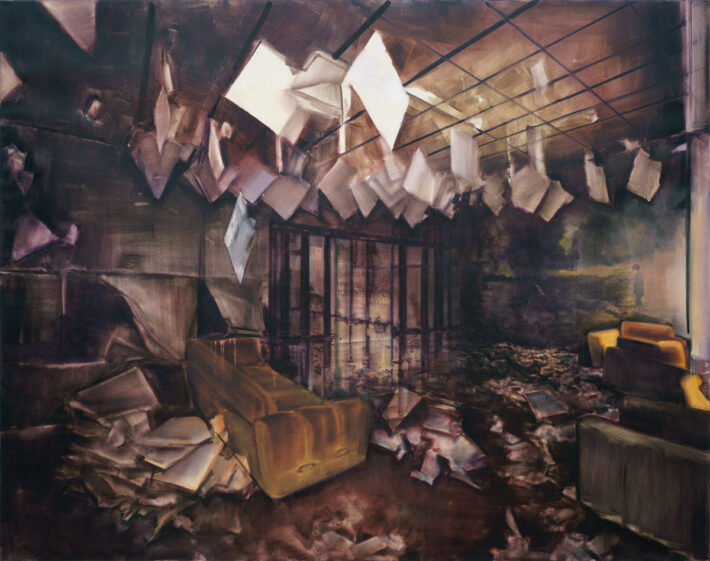

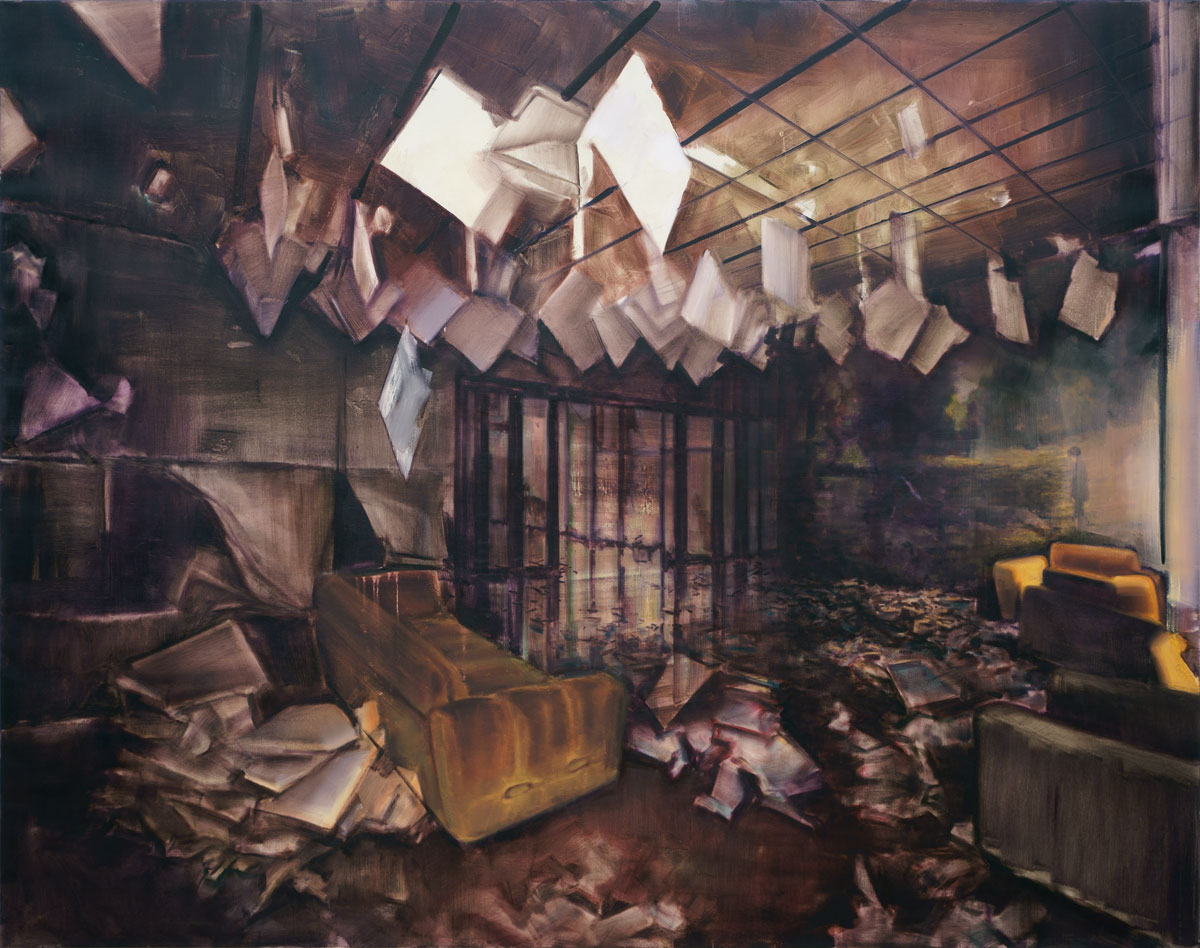

Later, the tangible blind spots have disappeared, but Szűcs also depicted Kádár’s holiday home as a blind spot in a figurative (epistemological and memory political) sense (Living room in the Kádár villa, 2014). The house in question was, in fact, deliberately forgotten and neglected, although it could be one, if not the most important lieu de memoire of the Kádar era.

Socialized in the atmosphere right after the regime change, amid the ongoing canonization of neo-avant-garde and the expansion of new media art in Hungary, the artist group Little Warsaw (Kis Varsó) was founded in 1996 by András Gálik and Bálint Havas. The group borrowed its name from a legendary area populated by Jews in the Eighth District of Budapest, where the resistance successfully fought against the Nazis and the members of the Arrow Cross (the Hungarian National Socialist Party) during World War II. Already at its inception, the group intended to systematically process the socialist past in their various projects rooted in conceptualism.

exhibition: “Who if not we.”/ Time and Again, Stedelijk Museum, 2004

photo: Stedelijk Museum

One of the most renowned of these works was Instauratio, where they erected the statue of János Szántó Kovács (1965) by József Somogyi (one of the most famous Hungarian socialist realist sculptors and, for a time, the rector of the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts) at the Stedelijk Museum’s exhibition Time and Again in Amsterdam in 2004. The title of the piece speaks for itself, as it is a hybrid of ‘installation’ and ‘restoration’, meaning that Little Warsaw (Kis Varsó) intended to represent themselves with the ideological-critical restoration of the statue of Somogyi at a post-communist exhibition in one of the most famous museums in Western Europe. Basically, they were asking, somewhat provocatively, what a Western viewer could do with the statue of a 19th-century Hungarian agrarian socialist revolutionary which, at first glance, appears to be just a stereotypical socialist realist peasant figure, while his undeniable power, monumentality and strange modernism also evokes the conflict not only between peasantry and the proletariat, but also between tradition and modernization.

Another of their works, Crew Expendable (2007) demonstrates a similarly fine microhistorical motivation that, in a global context, evokes the sci-fi classic Alien (1979) with the concept of a crew sacrificed for scientific discovery and profit, while actually thematizing the figure of a forgotten artist, János Major, and his so-called tombstone project from the sixties, when he found Jewish tombstones decorated with intertwining five-pointed and six-pointed stars.

exhibition: Unmistakable Sentences. The collection revisited.

Ludwig Museum – Museum of Contemporary Art, 2010

copyright©Ludwig Museum, Little Warsaw

The strange symbol for Major, who was of Jewish descent, became of interest on both a personal and an existential level, because he was very interested in the issue of the suppressed, or even taboo topic of Hungarian anti-Semitism. Major could experience anti-semitism first-hand as a forgotten and, in some sense, disenchanted magical realist graphic artist of the Iparterv generation (the best known group of artists and art history formation of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde). Almost turning into abjects, his parodistically anti-Semitic (in fact, anti-anti-Semitic) graphics could not be sufficiently deciphered not only by the official, socialist realist spectacle, but also by the liberal and modernist ideology of the neo-avant-garde, since in both systems only the universal had a place and a meaning, while the personal dimension seemed pathetic and petty. One could also say that both sides were trying to suppress the selfish and practical Eigen-Sinn, which, according to German social history, became the everyday ideology of the people of fascist and communist dictatorships. As the Szántó Kovács statue could be the portrait of the grumpy and wayward yet successful Somogyi, who cooperated with the system but still adhered to his own (modernist) ideas, so becomes the satirical drawing The Yid is Washing Himself (1967) a self-portrait of the disenchanted Major, who is being put on the pedestal of Little Warsaw’s monument as an emblematic figure.

Unmemorial is also a non-memorial with a similar spirit, which is not a traditional memorial, that is, not a memorial to the depicted worker, but an allegorical portrait of its creator.

exhibition: Naming You, Secession, Vienna, 2014

photo: Michael Michlmayr

The object of the artistic intervention is the statue Reading Worker (1951) by András Beck, which first appeared as a non-memorial at the exhibition of Little Warsaw, entitled Naming You (2012) at the Wiener Sezession. With a classically rooted figure – the pathos ranges from Dürer’s Melancholy to Rodin’s Thinker – Little Warsaw reintroduced the communist idea of the Cultural Revolution at an extremely complex exhibition into its original (no less complex) world of reality, which was covered by the intricate weave of desires, fears, ideologies, and compromises. András Beck was one of the typical figures of the communist world: a highly-cultivated sculptor with avant-garde ancestors, who, following the change of regime in 1949, also served the communist system due to his leftist commitment. He believed in the Cultural Revolution, which is aptly symbolized by the Reading Worker, and was disappointed by the communist dictatorship, degenerated to a personal cult that systematically cut off its enemies not only from power but even from the public (i. e. imprisonments, deportations). Little Warsaw, moreover, juxtaposed Beck’s career with another aspect of socialist culture, the scientific and technical revolution, in which modernization was, in part, truly in the interests of the people (as demonstrated by the Soviet potato harvesting machine appearing next to the compromising figure of Beck, a servant of the system), while violent collectivization destroyed the faith and commitment that socialism actually needed to succeed. This kind of critical perspective can be compared not only with the civilizational interpretation of revisionist Sovietology and the contextual approach of social art history, but also with the activist criticism of esoteric conceptual art.

A similar approach applies to the works of Tamás Kaszás, a graduate of Intermedia Studies and a follower of the social-critical, radical utopian thinkers (e. g. Tamás St. Auby, Miklós Erdély) of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde. Kaszás does not analyze art from a formal, neither a medial point of view, but explores its social potential, and was one of the first to turn to communist iconography with an entirely new approach, as exemplified by his piece entitled Broadband Bulletin Board (1998-2009). The reinterpretation of the well-known elements of the labour movement’s iconography (sickle, hammer, wheat, worker fist, worker heros), coupled with the latest ecology-driven critique of the late capitalist system, sheds new light on communist ideas, and frees the symbols of community culture from the captivity of negative connotations (violent, unreasonable, and hypocritical collectivization). Kaszás puts the anti-capitalism of communist ideas into an ecological perspective with the aim of creating a new ideology and iconology for survival, or, at least, sustainable development, or creating a new kind of “folk science” along the lines of folk art and folk culture, which is able to function in a new, hypermodern world of broadband connections.

The memorial entitled Burden or Resource? (2017) by Randomroutines (the artistic cooperation of Tamás Kaszás and Krisztián Kristóf since 2003) in Třinec, Czechia, is a haunting reminder of the human towers of the famous Czechoslovakian mass sports events, the Spartakiada. The title, on the other hand, is a quote from the human resources minister of the populist but anti-communist Orbán government: “Neither the Hungarian communities nor the government have decided whether the Hungarian-speaking Gypsies living across the border are a burden or a resource.” The terms ‘burden’ and ‘resource’ thus refer to the human factor, the human resource, which played a prominent role in the construction of the socialist spectacle. At the top of the human tower stands a young girl with a wrench as if she was installing something, which, however, only looks like a large cracked mirror. Originally, a socialist monument depicting the conquest of the cosmos was designed to be erected on the monument’s place resembling a grandstand. However, the heroic, iron-welded youth of Randomroutines, on their journey to the cosmos, do not rise to the stars because they collide with a cracked mirror, which, despite all their heroism and enthusiasm, cannot be repaired with the tools at their disposal.

Another post-communist iconologist, Csaba Nemes graduated from the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts as a painter during the change of regime. He later worked on neo-conceptual photo-based art projects, then painted storyboards and made animated films about political topics. The language of socialist or rather social realist painting returned to his work in this political context, as he first applied it in his pictures related to the series of Roma murders committed in 2008, which had caused a great uproar in Hungary, and politically supported everyday racism. However, in the series Father’s name: Csaba Nemes (2009-2013), through his own past and photographs of his father, he reflected on the conflict between cultural and communicative, that is, social and personal memory.

Csaba Nemes the older, worked as a member of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party (MSZMP), far from the capital, in a small village, Tuzsér, where he put his heart and soul into managing the school and the cultural centre, and as a result, his photographs portray a truly human-faced socialism. His son Csaba Nemes, on the other hand, selected photos that offer a glimpse into the slips and bumps of everyday socialist iconography as well as of the failures of the system, as his painting Hearing (2010) does. Following one, or rather two, regime changes, the viewer recognizes that not only the pioneer boy is incapable of finding his place in the system, but those in power do not really know what to do with the situation and the power vested in them either.

The direct antecedent of Nemes’s personal series, Kádár’s Holiday Home 1-4 (2009) reflected on a special element in the iconography of the number one leader: the pictures of this series specifically portray purist, modernist holiday homes (owned by Kádár and other senior leaders) located next to the lake Balaton in a realistic style, which pointed to a neglected aspect of the socialist past, its modernism, and its ambivalent relationship to modernism in the Western sense.

While in fine arts and in ideologically representative genres decomposition and abstraction were seen as decadent, in architecture, not only functionalism was promoted, but abstract ornamentation was also accepted. Recalling the drama theory and epic theater of Brecht and the spectacular ideology of all aspects of socialist life, Dialectical Theatre (2015) features another dimension of oblivion, an alternative sculpture park. The heroic socialist realist sculptures are standing on a deserted lot in downtown Budapest in the present, which is likely to be the site of a modernist, functionalist office building. An elderly woman is walking down the street, ignoring the statues of superhuman communist heroes deported to the midst of crumbling houses. Perhaps she doesn’t even see them anymore: on the one hand because she only cares about her own fate (Eigen-Sinn), and on the other hand because their symbolic and iconic power has long since vanished.

A fellow graduate of Nemes, János Kósa (similarly to Attila Szűcs) has already committed to painting in the neo-conceptual period of intermedia, photography and installations, and in the 1990s, he built his oeuvre on “digital” reinterpretations of classic and modern motifs in art history. In his case, however, ‘digital’ did not mean digitizing painting, but activating the pathos of the information society, that is, in Kósa’s paintings, hackers and painting robots took on the classic pathos formulas.

photo: Miklós Sulyok

During the international career of Neo Rauch and the New Leipzig School, Kósa incorporated both the official and unofficial, but popular icons of the socialist past into his works. For example, in Province (2007), dedicated to the subject of space exploration, not only do slender workers stretch out to the stars on a socialist modernist relief, but one can also recognize a legendary Hungarian cartoon character of the sixties among them, the rather simple than brilliant Köbüki, a distant (twelfth generation) future descendant of the Mézga family, who can be interpreted as a parody of the average Hungarian socialist family. A few years later, Offering (2010) went even further in the ironic treatment of the past, where an ancient topos of nationalist art provides the starting point: King Stephen, the first king of Hungary offers the crown, symbolizing the country, to the Virgin Mary to help protect Hungary.

The topos of Regnum Marianum (literally meaning the Kingdom of Mary) became especially popular during Romanticism and Historicism, when it was revived as a symbol of the desire for an independent Hungarian statehood. Gyula Benczúr, the most celebrated Hungarian academic painter of the 19th century, also painted the scene, and Kósa incorporated the angel representing the divine power of Mary to his own composition. In Kósa’s painting, however, Saint Stephen offers the (toy) crown to Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, while surrounded by various icons of the socialist era: a heroic communist sailor, a clown of the “communist” Picasso, and, as a late descendant of the clowns, another well-known Hungarian fairy-tale hero, the well-meaning Manócska, who is caring for the ageing Saint Stephen. The painting can also be understood as a genealogical reading of the success story of today’s Hungarian populism, as it shows the extent to which the people are addicted to the old topoi and gestures, as well as their exceptional ability to accept the anachronistic survival of feudal power structures.

Another aspect of Nachleben, the “purging” and activating of the critical potentials of communism, was the focus of the Société Réaliste group (Ferenc Gróf and Jean-Baptiste Naudy, 2004-2014), who also explored icons. Gróf and Naudy hosted their most significant solo exhibition Empire, State, Building at the Jeu de Paume in Paris, whose ironic, anthropological approach – juxtaposing the symbol systems of real and fictitious cultures – can be compared not only to that of the situationists but also to the revisionist Sovietologists. Also dealing with critical cartography, symbolic typography and psychogeography, the duo has produced 19?9 for a previous exhibition, Over the Counter (Műcsarnok, Budapest, 2010), which focused on post-communist economic life.

The work recalls the tortured figure of György Dózsa (sat on a hot iron throne), borrowed from the woodcut series 1514 by Gyula Derkovits (1928), the most famous Hungarian communist painter. Dózsa has become one of the symbolic figures of proletarian anti-capitalism, who, in fact, was a professional soldier hailing from an impoverished noble family. He became the leader of the peasant revolt of 1514, which, after a brief period of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919, became the number one historical precursor of the communist revolution in Hungary. The original, spiritually anti-capitalist, and even explicitly communist piece, was rewritten by Société Réaliste on the one hand, with the transcription of the allegorical commentary, that is, the ideological message (the text burnt onto the chest of Dózsa), on the other hand, by deconstructing the technique with which it was originally made. Dózsa’s crown no longer reads the date 1514, which referred to the suppression of the peasant revolt, but 19?19, which evokes the regime changes of the 20th century, linking 1919, 1949 and 1989, when both communist and democratic changes were accompanied by constitutional changes. The other textual change is even more thoughtful, since Dózsa is no longer labelled “stinking peasant” (büdös paraszt) but “stinking parallel” (büdös paralel – sic!), indicating that the logic of revolutions with different ideologies is too similar. However, Gróf and Naudy also conducted an in-depth analysis of the original engraving, as the shape of Dózsa is drawn from words, crossed out in black and red as a deconstructive gesture, taken from the 1989 democratic constitution, which actually only amended the text of the communist constitution of 1949, based on a Soviet model. Société Réaliste thus points out the haunting continuity of communist and post-communist life and reality.

Courtesy of the artists & acb Gallery, Budapest

photo: Miklós Sulyok

Another of their works deals with the geopolitical dimensions of continuity: the Empire State Building (1931) and the planned but ultimately unrealized Moscow Palace of the Soviets (1933) intertwine in Empire of Soviets (2011) using a distinctive medium of socialist realism, the not noble, but expressly ordinary, proletarian cut iron sculpture that evokes industry and the working class. The easily interwoven realms and buildings that are not very different from each other thus provide a critique of the spectacle through the exploration of symbol systems that conquer and dominate the imaginary, the imagination, and desires. However, its current 21st-century context is clearly global capitalism, whose criticism fits in with the intellectual aspirations of the New Left. Representatives of the youngest generation follow similar paths of memory politics, but the focus and the pathos have shifted somewhat. Similarly to Csaba Nemes, Olívia Kovács, whose career started in the 2010s, painted her parents’ family photos in the series The Other’s Past (2013). However, they are no longer coloured by tragedy, existential and ethical conflict, but rather by nostalgia and exoticism.

A contemporary of Kovács, Kitti Gosztola, amid the present spell of national populism, does not thematize the communist past any more, but rather the national conservative heritage. A cooperation with Oliver Horváth and Szilvi Németh, Compass (2017) no longer evokes revolutions but rather the Trianon treaty and national traumas, by presenting them in a new, ironic light as they used a marine biological metaphor to symbolize the breadth and irrationality of irredentist ideas. After Hungary lost its access to the sea, a Hungarian biologist was enraged about the lack of a fifth figure, symbolizing the lost seas, beside the allegorical figures of the ceded territories on the irredentist memorial on Szabadság tér (Liberty Square) in Budapest. Instead of the four Hungarian warriors caring for characteristic figures of the ceded territories, Gosztola and her companions created only a flower bed resembling a starfish as a kind of counter-memorial, replacing the allegorical figures of the original monument by a biological symbol capable of regrowing its limbs.

SKC Gallery, Rijeka (Croatia), photo: Dominik Grdić

However, Gosztola’s work was only on display at an exhibition in Rijeka, while a memorial was erected on Szabadság tér in Budapest to commemorate the heroic struggle against the German invasion of Hungary in 1944, conveniently neglecting the fact that the Hungarian army and part of the Hungarian population were actively involved in the Holocaust. The distorted image of history that the Szabadság tér memorial represents prompted many of the artists mentioned in this article to speak out, protest, and engage in activism.

SKC Gallery, Rijeka (Croatia), photo: Dominik Grdić

Moreover, it drew attention to the fact that, in line with the latest endeavours of official memory politics, there are pieces in the oeuvres of Hungarian post-communist iconologists that do not lift the socialist past out of history, but to reintroduce it into a continuous historical stream of emotions and feelings, images and narratives. A typical example of this would be the aforementioned Offering, whose pathos spans from King St. Stephen and the Catholic Church’s icons of Byzantine origin, through the socialist realism of Stalin and Rákosi to the pop culture of the sixties. But in this spirit, we can also discover the figure of the Pantokrator and the Hungarian holy kings in Dózsa, sitting on a fiery throne, as well as in the unfortunate androgynous clone of Société Réaliste. Perhaps the most perfect Hungarian allegory of the postmodern triumph of iconology, however, might be an installation of Little Warsaw, The Battle of Inner Truth (2011), in which, in the world-wide archive of war-themed sculptures borrowed from Hungarian museums, under the auspices of the Babylonian ziggurat and some fluffy pillows, all the pathos formulas from Roman gladiators and conquering Hungarian warriors, through Dózsa and his warrior peasants, as well as the heroes of the labour movement, to a World War II aircraft smashing into a Gothic tower, are peacefully playing with each other.

exhibition: Private Nationalism. Kiscelli Museum-Municipal Picture Gallery, Budapest, 2014

photo: Lenke Szilágyi

The enigmatic title, however, not only presents the migration, afterlife, and reinterpretation of motifs as the most natural human and artistic activity, but also intensively plays on the psychic dimensions, from real pathos through artful artistic compromises, to the disenchanted, painful, schizophrenic re-creation of images. The registers of this psychic spectrum are the ones that make the post-communist iconology of communist iconography, which was perhaps the basis for one of the most exciting artistic trends in the Central European cultural region (that has been shaped in the spirit of classical visual culture), really enticing.