Róza Tekla Szilágyi

Labour is a treat in itself when you enjoy it

The precarious conditions of art jobs in Hungary

Although creative professions are often accompanied by a sense of vocation and a passion, sufficient working conditions are rarely guaranteed for those in these fields. This uncertainty raises the question of whether there is an overlap between the social class of the precariat and the group of people engaged in creative work, including artists. Through the works of three artists, I examine the relationship between the effects of precarious conditions and immaterial and theoretical work, as it creates determining situations both in a professional and an existential sense in today’s active art scene.

Artist-as-labourer vs. artist-as-entrepreneur

Artistic activity and creative work often appear before us as manifestations of total freedom and boundlessness. It is important to emphasize that while the mobility of artists and curators, resulting from certain projects, residency programs and institutional collaborations (as well as the pursuit of such opportunities) is common in the art world, this freedom of mobility also presents professional difficulties. As international mobility has grown, curatorial and artistic professions became synonymous with leading the life of a tramp – therefore, excursions for research purposes or pop-up projects generated in unknown areas may have contradictory effects.

What does the “tramp” lifestyle provide? Breaking into the international art world existing in the network of digital society and prevailing in that market relies primarily on visibility and presence, that is, to get more people at more places to see the work of a given artist – these are the opportunities that the “tramp” lifestyle provides.

However, before a work of art reaches a state of being ready to be exhibited, before a performance becomes watchable, before the first printing press starts, and before the first 3D design is created, it is preceded by invisible, imperative and often difficult-to-calculate tasks. Purchasing the necessary equipment and the materials, the hours spent planning, securing a suitable location, setting up and briefing the team, obtaining and studying the necessary literature – we could go on and on. Whether the end result is an object, a document, a gesture or a performance, its birth is always the result of labour. This activity often expands to seven-day working weeks and a seemingly flexible schedule, which, more often than not, is only a cover for constant activity. Several initiatives provide behind the scenes insights: the increasingly popular studio visits (such as the Afternoon of Open Art Studios and the open days of Art Quarter Budapest as well as the events of Budapest Art Week), the public theater rehearsals, and the videos providing insight into the daily lives of art professionals serve, among other things, the very purpose of raising awareness to certain elements of these hidden activities in the minds of end users and consumers alike. The twist in the story is that, just as the work done in traditional Fordist factories is not visible to those outside the factory, so are the products of artistic institutions that are understood as factories rarely seen outside these locations. Institutions born to present products thus generate a paradoxical situation. With a little exaggeration, the artworks and the work done there is as visible as the workflow of any traditional factory.

The question arises whether, in the context described above, the artist’s character – instead of the genius figure of Romanticism, which is often referred to this day outside of the art world as the typical example – can be characterized as a worker or rather as an entrepreneur? Regarding creative professions, the first thing to mention when it comes to maintaining creativity and motivation is the state of precariousness. It is this precariousness that often indicates the difference between material labour resulting in a market-based, tangible product satisfying a specific need, and between immaterial labour (although this picture is becoming more and more subdued with the use of 0-hour contracts, which is also common among material labourers).

The most important points of the interpretation of the word ‘precariat’ in relation to this current topic were summarized by Sándor Hornyik: in Franco Bifo Berardi’s interpretation, the precariat – as opposed to earlier interpretations less related to creative work – already appears as a class of creative freelancers with a flexible schedule, conducting immaterial labour. Sándor Hornyik goes on to say, “Brian Holmes, who is a bit more familiar with the art world than Bifo, sees the situation of artists much darker. In his essay, ‘The Flexible Personality’ (2001), he writes about the global information society’s success in personality-shaping, which has slowly transformed the art industry similarly to the creative industry.” This means that as surveillance techniques have been evolving in a remarkable way, wage labour and freelance labour – whether done locally or remotely at telematically connected sites – has also become the subject of surveillance (i. e. email tracking applications, surveillance cameras, call control).

Brian Holmes further refines his explanation of freelancers’ vulnerability: “The offer of freelance labour, on the other hand, can simply be refused if any irregularity appears, either in the product or the conditions of delivery. Internalized self-monitoring becomes a vital necessity for the freelancer. Cultural producers are hardly an exception, to the extent that they offer their inner selves for sale: at all but the highest levels of artistic expression, subtle forms of self-censorship become the rule, at least in relation to a primary market.”

Thus, the information society in which we live also shapes the creative and art industry in terms of its customs. But besides customs, capitalism also influences the constellation responsible for taste and values. As Richard Florida, an American urban studies theorist who focuses on social and economic theory, says, “creatives” are a conscious class whose behavior is difficult to predict and cannot be deflected. These qualities are most likely the result of uncertain conditions affecting creative professionals, since they demanded awareness from the members of the precariat. Due to the very nature of the new creative economy, jobs and opportunities come and go, thus, security is the privilege of the few.

Artists living in Hungary are seeking connections with the international art world not only for the sake of wider visibility, rather for more seriously funded opportunities, essential for their livelihood, due to the small size and the small art scene of the country. However, building foreign relationships requires a broader artistic practice as well as an entrepreneurial mindset more typical of marketing professionals. The factor that makes it even more difficult to master the artist-as-entrepreneur mentality is that the active segment of the Hungarian art scene seems to exist as a parallel reality, with little connection to the everyday world – that is why the creative labour conducted in this parallel reality is more difficult to interpret for groups that actually have capital and are able to provide support to artists.

The concept of art jobs in the light of immaterial labour

Although fine art cannot be called literally intangible labour, since artistic activity produces tangible (sic!) objects, the social acceptance of the creative process and the reactions and scepticism of lay people who are less familiar with the relationships of immaterial labour are in many ways similar towards professionals carrying out immaterial and theoretical work.

According to Guy Standing, “The precariat has distinctive relations of production […] Essentially, their labour is insecure and unstable, so that it is associated with casualisation, informalisation, agency labour, part-time labour, phoney self-employment […] All of these forms of ‘flexible’ labour are growing around the world. Less noticed is that, in the process, the precariat must perform a growing and high ratio of work-for-labour to labour itself. It is exploited as much off the workplace and outside remunerated hours of labour as in it.” Italian sociologist and philosopher Maurizio Lazzarato, who coined the term immaterial labour in 1996, emphasizes that “It is worth noting that in this kind of working existence it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish leisure time from work time.” Conclusively, succeeding in art is a full-time job and requires an attitude similar to that of an entrepreneur leading their own business. Due to the varying intensity of working hours which are not easily trackable in a traditional spreadsheet, activities producing cultural content are usually harder to interpret as labour. As Lazzarato states, “All the characteristics of the postindustrial economy (both in industry and society as a whole) are highly present within the classic forms of ‘immaterial’ production: audiovisual production, advertising, fashion, the production of software, photography, cultural activities, and so forth. The activities of this kind of immaterial labor force us to question the classic definitions of work and workforce, because they combine the results of various different types of work skill: intellectual […], manual […] and entrepreneurial skills.” It is important to emphasize that immaterial labour mostly exists in the form of networks and it never operates at a specific location (i. e. the factory), but in society at large, and it is here that it acquires its legitimacy. The fragmented nature of creative labour requires small, productive “units” organized specifically for the tasks of an ad-hoc project. These groups may exist only for the duration of those particular jobs (think exhibitions, plays, or cultural festivals existing outside permanent institutions).

The global production of fine art is characterized by intermittent work, fragmented labour and wages in most places – this is especially true of the small Hungarian market, which is unfortunately lagging behind in many respects in terms of visual culture consumption. The situation of major museums closing in succession for various reasons (renovation, relocation), the questionable quality of public artworks, and the financing difficulties for emerging fine arts initiatives and groups all contribute to the inaccessibility of fine art for the broader public. Thus, it is not surprising that the actors of the Hungarian fine arts scene encounter significant systemic deficiencies during their work that seriously hinder their advancement, which they must remedy themselves with personal activities and engagement in order to alleviate precarious conditions. Along these lines, we can conclude that Hungarian artists trying to break into the international scene need to acquire the artist-as-entrepreneur attitude.

Zsolt Asztalos – unknown artists and canonisation

With respect to fine art – in the era of “a child could paint that” type of commentary especially typical in the case of abstract paintings and graphics –, the question rightly arises: “wherein lies the intellectual or cultural added value of such work?” As Dirk van Weelden states, it would seem that artists “carry out an alternative […] form of research and journalism. Consciously and with critical intent, in order to provide a necessary supplement […] for the information and images that circle around us.” He also adds that “Culture has been an industry for a long time, and therefore a market as well. Creativity is a commodity, inside and – above all – outside the art world.”

But how did this all happen? There is always a demand for nice things and eye-catching decorations, however their quality is a whole another question. The global flow of information has spawned a worldwide market based on an artistic practice consisting of (thoughtful, multi-component) creativity and years of institutional and extracurricular studies, as well as the ability to produce an aesthetic product available at IKEA’s decoration department. The world of art has its own “network with its own flow of funding, its own publicity, its own complex relationships with governments and financiers. Works of art are what is discussed and displayed in the spaces and publications belonging to the network. Artists are those who are active and show their work and receive reviews and invitations within that world.” Meanwhile, “the communication economy aims to make every consumer a producer as well, of photographs, music, messages, public outpourings, performances, videos, opinions and stories.” These more commercial manifestations are on the market in the same way as the products of the fine art scene – just think of the new group of artists, tattoo artists and graphic designers who are active only on Instagram.

As mentioned earlier, a successful fine arts career requires creating publicity and maintaining a presence. Several works of Zsolt Asztalos resonate with this idea and the question of non-artistic images created with the help of digital platforms and widespread imaging tools.

Winner of the Mihály Munkácsy Prize, Zsolt Asztalos (1974) graduated from the Hungarian University of Fine Arts in 1999 in the class of Dóra Maurer. Primarily a conceptual artist, his works have previously dealt with the situation of the everyday person within consumer society, but in recent years he has addressed various aspects of individual and collective memory. He mainly creates installations, videos and photo-based works. So far he has participated in nearly a hundred exhibitions both in Hungary and abroad. In 2013, he represented Hungary at the 55th Venice Art Biennale with his video installation, ‘Fired but not exploded’.

The rules of the art world, which operates in parallel with the capitalist market, but as a parallel public, and the evolution of the canon are all decisive factors in judging artistic labour. (It is in this context that a cultural financing system that provides more prominent financial support to artists echoing current pro-government ideas may seem really defective.) The various factors and issues determining the contemporary evaluation of works of fine art also appear in the oeuvre of Zsolt Asztalos. The central issue in his series Unknown Artists (Ismeretlen szerzők), the latest edition of which was shown in the ISBN Gallery run by Bea Istvánkó, is the significance of the artist persona and whether they can be separated from a particular work of art, as well as the extent to which the work is linked to the context created by the artist’s name. The exhibition features reproductions of works by unknown artists collected by Zsolt Asztalos; the arrangement, without the intention of visibility, evokes the moments before installation as well as moving house, the spaces of archives and warehouses, with pictures hidden halfway by packaging materials and bags.

Photo: Zsolt Asztalos, Courtesy of Ani Molnár Gallery

A controversial topic in art theory for centuries, Zsolt Asztalos turns towards the unknown author as a contemporary of a culture that plays with the idea of artist superstars whose image is built on a similar marketing strategy used for products of a competitive market. In a world where we encounter a constant flow of images thanks to the digital society and the everyday use of digital devices, we can easily identify the source and author of images created using such tools via the Internet.

While in the case of works from bygone eras, the case of unknown authorship does not necessarily reflect the will of the artist, in contemporary art the same situation is the result of a conscious decision and a well-built marketing strategy. Alongside unknown contemporary masters who are only identifiable by their work, there are also those who, by concealing their own names, decide to join a group – so that their own identity blends into a larger creative process driven by multiple factors.

Photo: Zsolt Asztalos, Courtesy of Ani Molnár Gallery

Zsolt Asztalos turns to those who have not even left their most basic mark of identification, that is, their names, on their creations. In the case of older works, the lack of signature may be caused by a number of technical reasons, such as the signature fading away or even being cut off, in addition to the artist’s decision. In the case of unsigned works, authorship can be revealed as a result of a number of parallel processes, if professionals have enough information about both the artist and their oeuvre in which they intend to embed a certain piece. By comparing stylistic elements and conducting archival, database and scientific research, professionals can attribute the works with the help of traces (brush strokes, the paints they used) left by the author.

The first version of the exhibition presented in the ISBN books+gallery had been displayed in the Bázis Gallery in Cluj-Napoca in autumn 2017: as part of that exhibition, which bore the same title, Zsolt Asztalos also debuted a documentary in which he explored the historical and contemporary theoretical aspects of the unknown author by interviewing several aesthetes, art historians and art experts. The works of the 2019 exhibition Unknown Artists raise not only the issues of historical research, but also important questions for shaping the contemporary canon: is the name of the artist an essential part of the truth of art? Is there a masterpiece in the absence of an oeuvre? Does a successful oeuvre create the context for a piece? And the question rightly arises: are the works of Zsolt Asztalos signed? In an age where an increasing number of people are able to create aesthetically pleasing visual content with the help of digital tools, Unknown Artists thus reflects on the phenomenon that signatures, which can be interpreted as an important element of artistic self-management, are playing an increasingly important role.

Courtesy of Ani Molnár Gallery

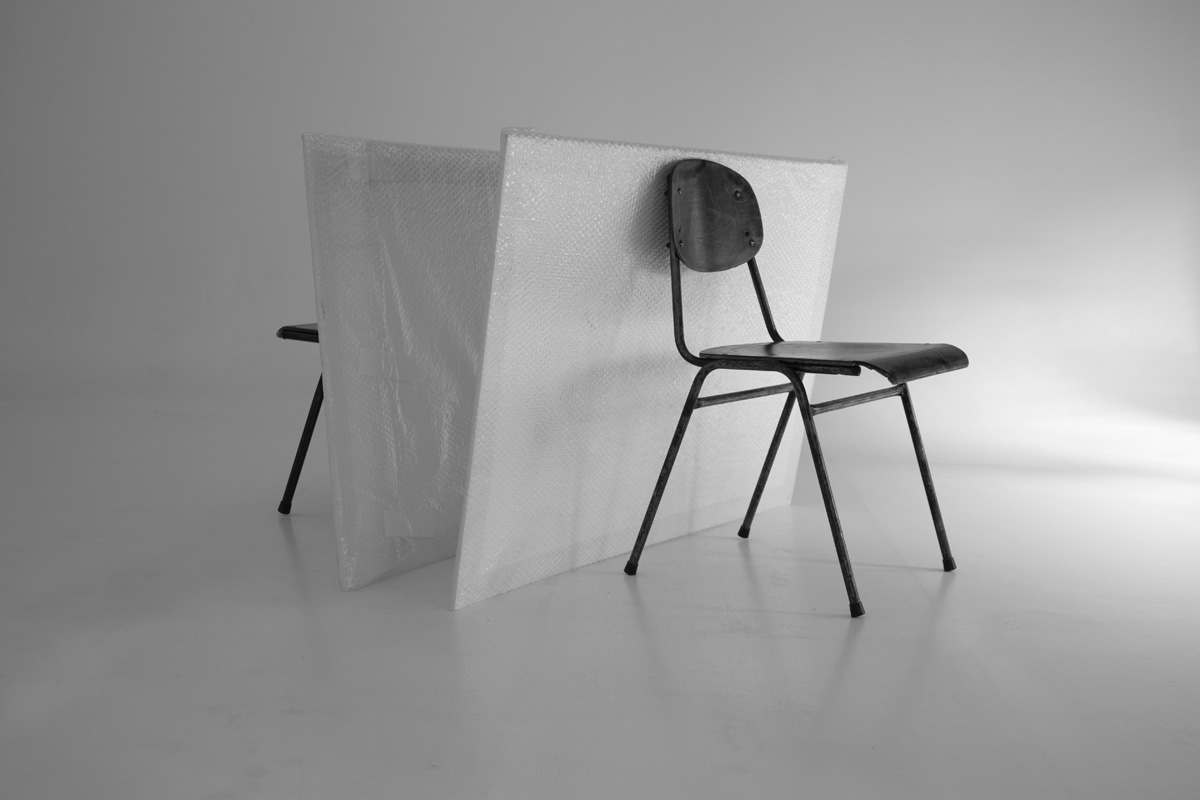

The series My Art consists of objects reminiscent of minimalist studio still lifes built of the artist’s earlier works; however, the peculiarity of the series is that only the frame of the works or, in some cases, only their shape, wrapped in packaging foil, is visible. No trace of the artist’s hand can be seen on the works, they can only be recognized by the composition they are arranged into. Pictures put in identical frames and larger prints covered with bubble wrap are recycled by the gesture of arranging them into an installation – Zsolt Asztalos reflects on the fact that entering the canon is beyond the control of the artist. After all, his works take on a new context as part of the installations in the way that certain elements of an oeuvre are put in new contexts in exhibition situations that disregard the artist’s original intentions. On some of the series’ pictures, we can see packaged works, or compositions typical of the studios, reminiscent of the state of packing before the transportation of the pieces. These conditions may be indicative of the artist’s presence at international fairs as a success factor in the art scene, a sign that the artist has successfully created his own publicity and that his work is being presented to a wider international audience. In contrast, the very same gesture of packaging may indicate that the work are lying forgotten in a dusty warehouse hidden from the eyes of the public.

Courtesy of Ani Molnár Gallery

Marcell Esterházy – the place of invisible work

As Gregory Sholette writes, “Even relatively successful artists must cope with constantly shifting employment, global transit […], and tireless networking and self-promotion.” Based on these qualities, Sholette calls artists “the prototype of the knowledge proletariat.” The precariousness of the very existence of those engaged in fine arts is mainly manifested in the inferior existential status of professionals and cultural workers active in this field. One of the most unique currencies in the fine art world, the opportunity, the hope of a future exhibition, or simply an opportunity that arises at a more distant point in time easily replaces an actual living wage. This means that those who are active in this field tend to take advantage of opportunities for their professional development, pushing real salary aside in the hope for long-term success – since the closed art world applauds these kind of choices the loudest.

At this point, a previously mentioned issue reappears. It is common for members of the precariat to have to work to get a job. The equivalent of this in the world of fine arts is the (often not professional) labour carried out for raising the rent of a studio. The situation is similar to that of the chicken and the egg: without a studio it is often difficult to work, but without work it is difficult to manage the financial constraints of renting a studio. And let’ not even mention the costs of art supplies, traveling for research, and buying the latest publications.

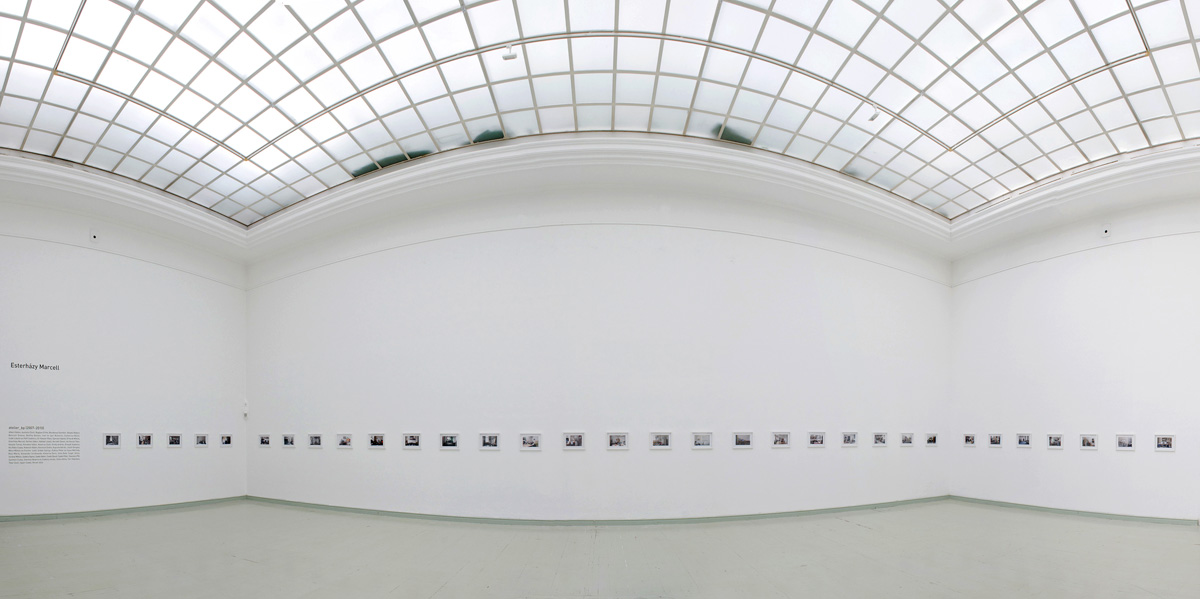

In his series entitled atelier_bp (atelier Budapest), Marcell Esterházy deals with the aforementioned subject. The series of photos, taken between 2007 and 2010, document the workplace of Hungarian artists, creative professionals and art theorists – but none of the photographs in the series actually shows the person using the studio, study or atelier.

“M. E. What a peculiar monogram – the last remarkable person who had these initials in Hungarian art was Miklós Erdély.” Currently living and working in Budapest, visual artist Marcell Esterházy was born in 1977. He graduated from the Intermedia Department of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts in 2003, and from 2014 to 2017 he was a student at the Doctoral School of the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. In 2004 he received the mention spéciale du jury of the Lucien Hervé and Rodolf Hervé Prize so he could study in Paris, as well as the Eötvös Scholarship which allowed him to take part in a post-graduate course at Le Collège Invisible, l’Ecole Supérieur des Beaux-Arts in Marseille. His works can be found in the collection of the Ludwig Museum and the Hungarian National Museum as well was the Irokéz Collection in Hungary, while abroad at the Marseille Fonds Communal d’Art Contemporain (FCAC). The recurring issues of Esterházy’s works include the varieties of processing the past, collective and personal memory, the demagogic fabrication of historical memory as well as the decimation of personal memory – so he often works with and reinterprets family photos and found albums.

The dilemma of “working in order to get work” is also characteristic of the issue of acquiring a studio. After all, the studio, which provides suitable conditions for creative work, puts a financial burden on its tenant. If we approach the art world from a strictly market-based point of view, then we can refer to the previously mentioned Fordist factories, where the work done in the factories is not visible to outsiders, as parallels of the atelier.

Marcell Esterházy gives an insight into the “factory” – that is, the world of the studio –, but does not provide any hints as to how the professional working in the studio earns the income necessary for maintaining the space. Is their fine art practice sufficient to secure the studio, and if not, what kind of “extra-curricular” activities are they doing to raise the rent? We do not know the schedules of the persons concerned – we only see that, for some, the place of art-related work is nothing more than a single desk in an average living space, while for others, we get an insight into the space specifically designated for such activity.

The viewer becomes a guessing voyeur – while Marcell Esterházy, as an artist, creates a photo series of studio visits that are increasingly popular in the art scene. The scene of the invisible intellectual labour becomes visible – what is more, the ateliers eventually find themselves presented as framed images in an exhibition space. Marcell Esterházy’s artistic role was to observe the phenomenon, select and document the locations, and finally then bring them to the exhibition space. This meta-translation and the lack of vocabulary associated with multiple translations are specific to Esterházy’s works.

Viktória Balogh – the traces of invisible intellectual labour

In the works of Viktória Balogh, the often invisible intellectual work carried out in the atelier is materialized in pictorial form through the medium of photography.

Born in 1992, Viktória Balogh is primarily engaged in conceptual photography, but she has been working with fine art techniques in many of her works. In 2017, she graduated from the Photography Department of the Rippl-Rónai Faculty of Arts at the University of Kaposvár, then continued her MA studies there. Between 2016 and 2019 she was a recipient of the State Scholarship of the Republic of Hungary as well as a fellow of the New National Excellence Programme. In 2018 and 2019 she was a fellow of the Hungarian Association of Photographers. She currently lives and works in Budapest. She had solo exhibitions in Budapest at the Hybridart Space and the ISBN books+gallery.

In her work Exercise Books (Füzetek), Viktória Balogh uses notebooks whose original purpose was to record and make it easier to recall high school curriculum – she repurposes them into handmade paper sheets with a traditional method. The words of the original notes sometimes pop up on these thicker and somewhat more worn, but clean sheets – fragments of the knowledge once recorded are thus recalled even after the notes have lost their function, referring to the phenomenon of “what you once learned, you do not forget completely”. The cycle of knowledge, the learning process that can be considered as intangible labour, and the accumulation of acquired knowledge are visualized in Exercise Books. These blank white pages can thus be interpreted as memorials of immaterial labour, of former teachers and of the hours spent studying.

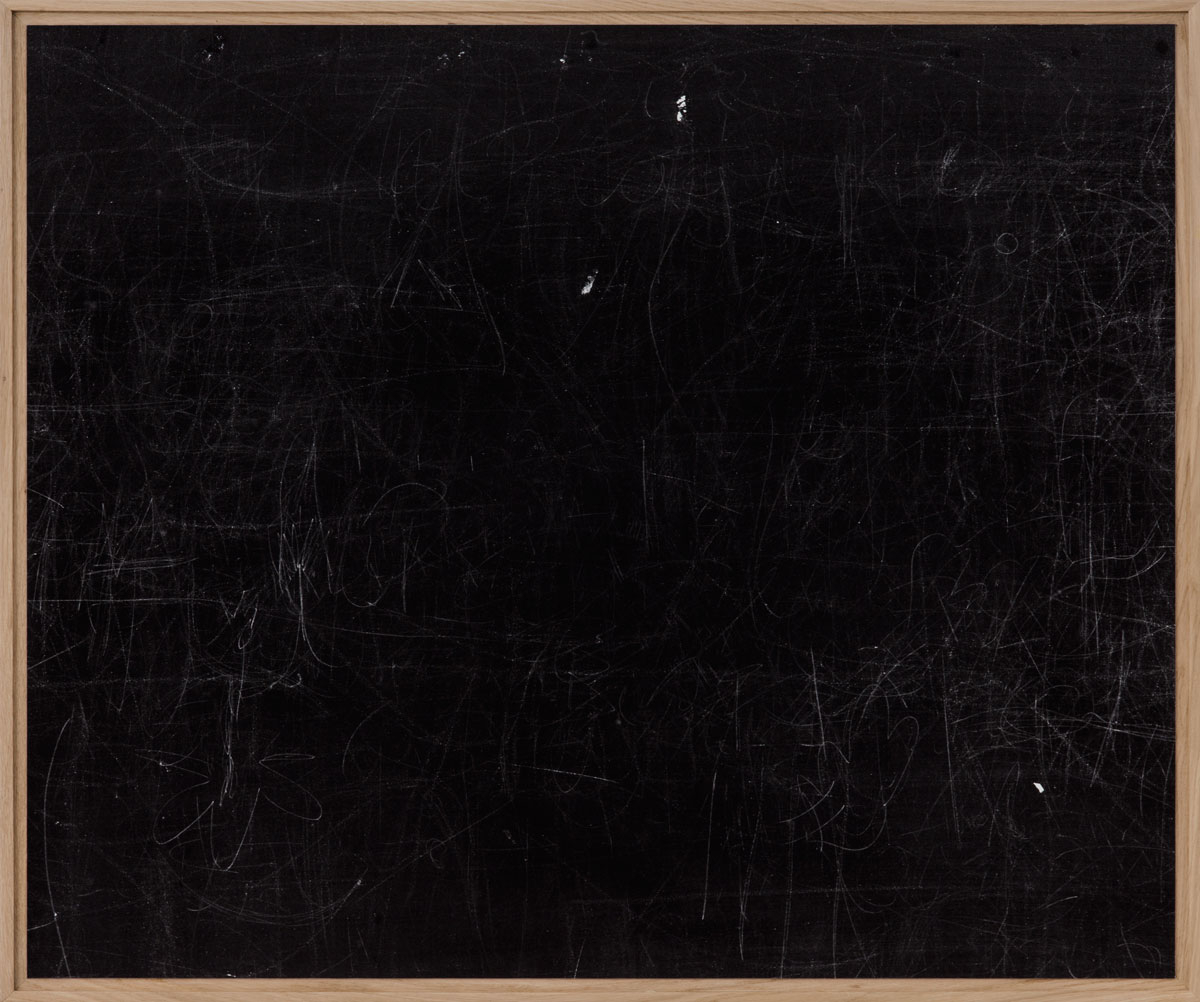

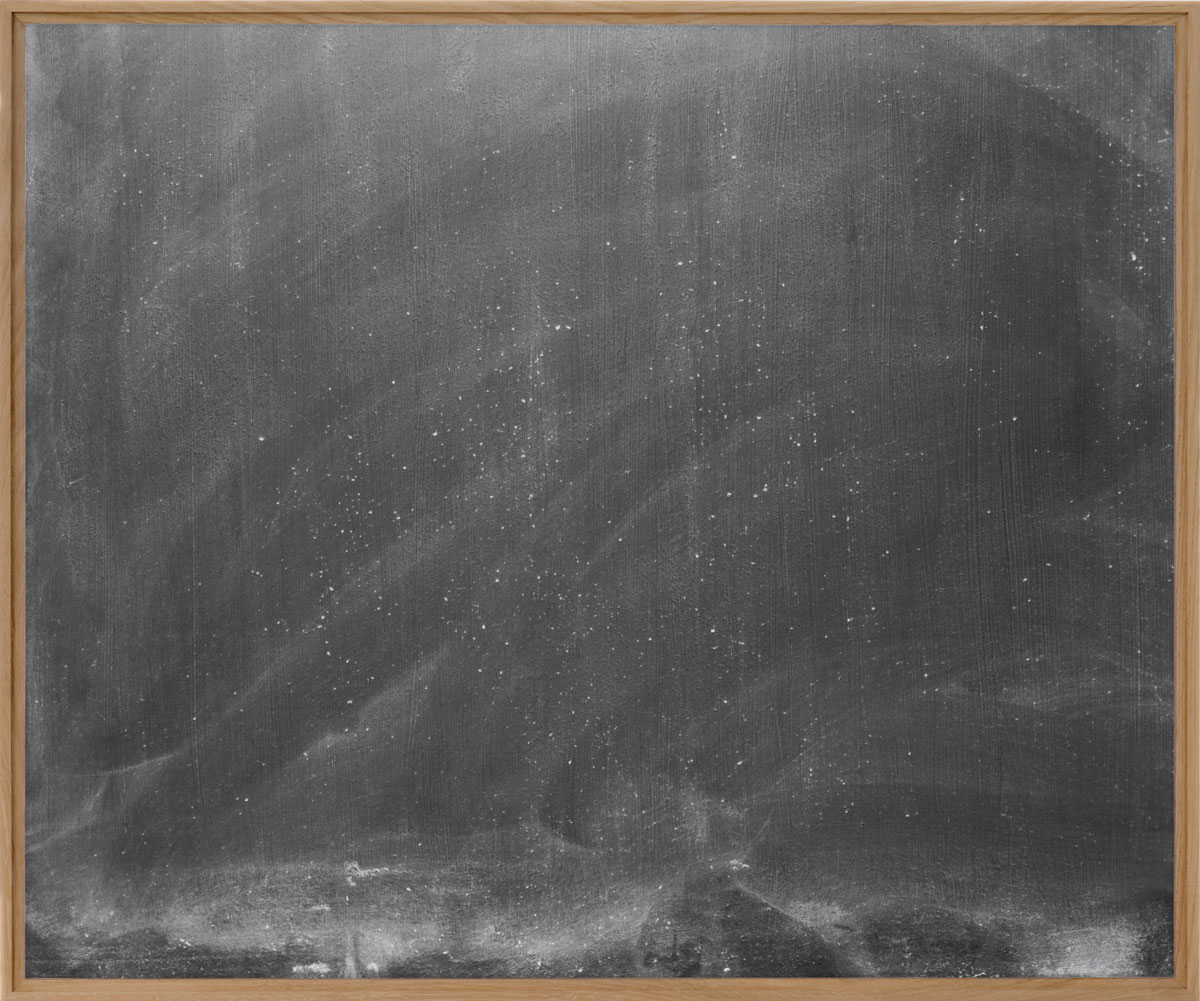

While Exercise Books focus on acquiring knowledge, photos of wiped-down blackboards and top-view images of scratched theatre stages focus on knowledge transfer.

The pieces in the series Knowledges, whose images are displayed in larger sizes resembling blackboards, symbolize theoretical and practical knowledge. The immaterial labour carried out at both locations – in front of blackboards and on the stages – is invisible in the pictures, as the actors are not depicted. Viewers can see only the layered clues, the signs of labour, left behind by those conducting the activities. Viktória Balogh’s works explore the possibilities of the visual representation of knowledge, reflecting on what is considered an unpaid, immaterial labour that we all carry out for our own development – and that, if they are fortunate enough, is present throughout the lives of both emerging and acclaimed artists so they are able to maintain their creativity.

The information society still believes in creativity and the economic benefits it can bring, and that almost a whole section of society can prosper solely through their creativity. Of course, creativity and the belief in it are constantly changing – nowadays, more and more creative professionals (both artists and art theorists) are trying to adopt the revenue models of the private sector. Thus, the artist-as-labourer has become an artist-as-entrepreneur, a free agent who, like other creative labourers, strives to adapt to the rules of the environment for greater financial security.

While international professional relations seem to be important topics for contemporary artists, the art world as an enterprise is still happy to take advantage of unregulated employment conditions. The precarious nature of international labour is not only a trait worthy of attention by artists, but also seems to be a structural necessity that allows the art world to continue to develop and expand. It is no coincidence that questions regarding the workings of the art world – its reliance on short-term contracts, the unpaid internship positions, the flexible working conditions and the lack of security for workers involved in the production of artworks – emerge all the time. Moreover, as Anthony Downey sasy, “Sustaining the culture of the art world is itself a business based on often inequitable terms of employment.”

The Hungarian art scene is also a dynamic system that adapts, but at the same time it breaks itself down to uncover contradictions within its own system. Institutions (museums, schools, galleries, exhibition spaces) “are rife with administrative malfunctions”, as Gregory Sholette puts it. A significant part of the institutional system of art depends on the money of the rich, the investors – so this factor also determines the relative safety of the precariat. Especially because, as mentioned earlier, private organizations and investors are much more reliable in meeting social needs than the public sector (it’s worth remembering the concept of artist-as-entrepreneur).

The decision is not simple: do you participate in this economy or do you leave it behind completely? Often conducting immaterial labour and living under precarious conditions, freelancers who exit the system are constantly working to get close to the source of capital essential to their work and well-being. Thus, in the search process driven by survival, members of the precariat strive to carry out self-assigned tasks related to their true interests, while seeking their own path – and finding and completing those tasks requires genuine creativity.