Zsófia Danka

Arts venues from the neo-avant-garde to the present

The dynamics of the contemporary Hungarian art scene can be best understood by exploring its arts venues and the professional directions of operation they are taking. Knowing the works and professional goals of the artists associated with each institution will help one understand the exhibition trends of galleries and museums. The international attention surrounding Hungarian artists is highly dependent on their debut as well as their professional environment in their home country.

1979/2011, silver print, 20x20cm, ed5

collection of Tate

The only kind of art that can affect us is the kind that we can connect to in some way. However, understanding contemporary art and getting close to it does not happen overnight. As we find ourselves in a white cube space or in a huge museum, it can be quite frustrating to be suddenly faced with the challenge of having to learn a complex language that combines art history, aesthetics, sociology and history at the same time. That is why it is important to be aware of the nature of the sociocultural changes of the local, that is, the examined community. If we go even further, and specifically try to understand the art of this small Central Eastern European country today, we need to look back over the last fifty years. The global visibility of outstanding representatives of contemporary Hungarian fine art as well as the international success of the young generation of artists all prove that it is worthwhile and important to pay attention to what is happening in our country.

In the first part of this article, I outline the history and evolution of Hungarian fine art from the neo-avant-garde to the regime change (i. e. the end of Communism in Hungary). The heroic rebellion of the seventies, the progressive subcultures of the eighties, and the softening pop culture of the nineties put contemporary Hungarian fine art on an internationally sound footing. The arts venues, the creative communities, and the opportunities and visions of professionals from public institutions play a key role in presenting valuable examples of contemporary art. This was the case during the years of the socialist dictatorship, and it is still the case today.

Photo: Miklós Sulyok

Following this introduction to a very unique part of our cultural history, I will look into the most important art institutions, galleries and museums any traveller coming to Budapest must visit as well as the professional events one can attend. Moreover, the list includes a couple of venues that could be considered ‘underground’ (i. e. a bit farther away from the mainstream) – visiting those practically makes one a native insider.

From the neo-avant-garde to the regime change

Hungarian neo-avant-garde art is quite difficult to understand without knowing its political background. Between 1957 and 1989, during the years of the socialist dictatorship led by János Kádár, the artists of the era faced many challenges. The ideological structure of the system greatly influenced their lives and career opportunities. Hallmarked by György Aczél, the gradually loosening state cultural policy of the communist era was determined by the system of three T’s, namely “Tiltott, Tűrt, Támogatott” (Forbidden, Tolerated, Supported). While some artists were eligible for state sponsorship, others had to make a living in more unofficial ways. Manuscripts ready for publication were returned to the bottom of the drawer, many exhibitions were banned, houses were searched, and many people were fired from their jobs. Some sensitive issues for the government, including criticism of the dictatorship, the issues of the working class, poverty, the country’s debt, the 1956 revolution, the Soviet occupation, the situation of ethnic Hungarians living outside the borders, as well as the persons of János Kádár and the main party and state leaders, were taboo. Tolerated artists had only the opportunity to organize exhibitions at their own expense, without any “advertising”, at the Adolf Fényes Hall or at the Young Artists’ Club (FMK), a significant semi-public venue of the era.

ef István Zámbó artist’s opening exhibiton, 1983

Photo: Fortepan

The Adolf Fényes Hall served as an official exhibition space for artists who were not considered worthy of support by cultural policy. The system of the so-called “self-paid” exhibitions was established here, which meant that unsupported artists and their experimental endeavors were also given a chance of public visibility. The Adolf Fényes Hall, whose exhibitions were organized by the Műcsarnok (Kunsthalle) from 1954, was home to exhibitions by such notable artists as Béla Kondor (1960), János Fajó (1968), Lajos Kassák (Picture Architecture, 1967), Imre Bak and Gyula Konkoly (1970), or György Jovánovics and István Nádler (1970).

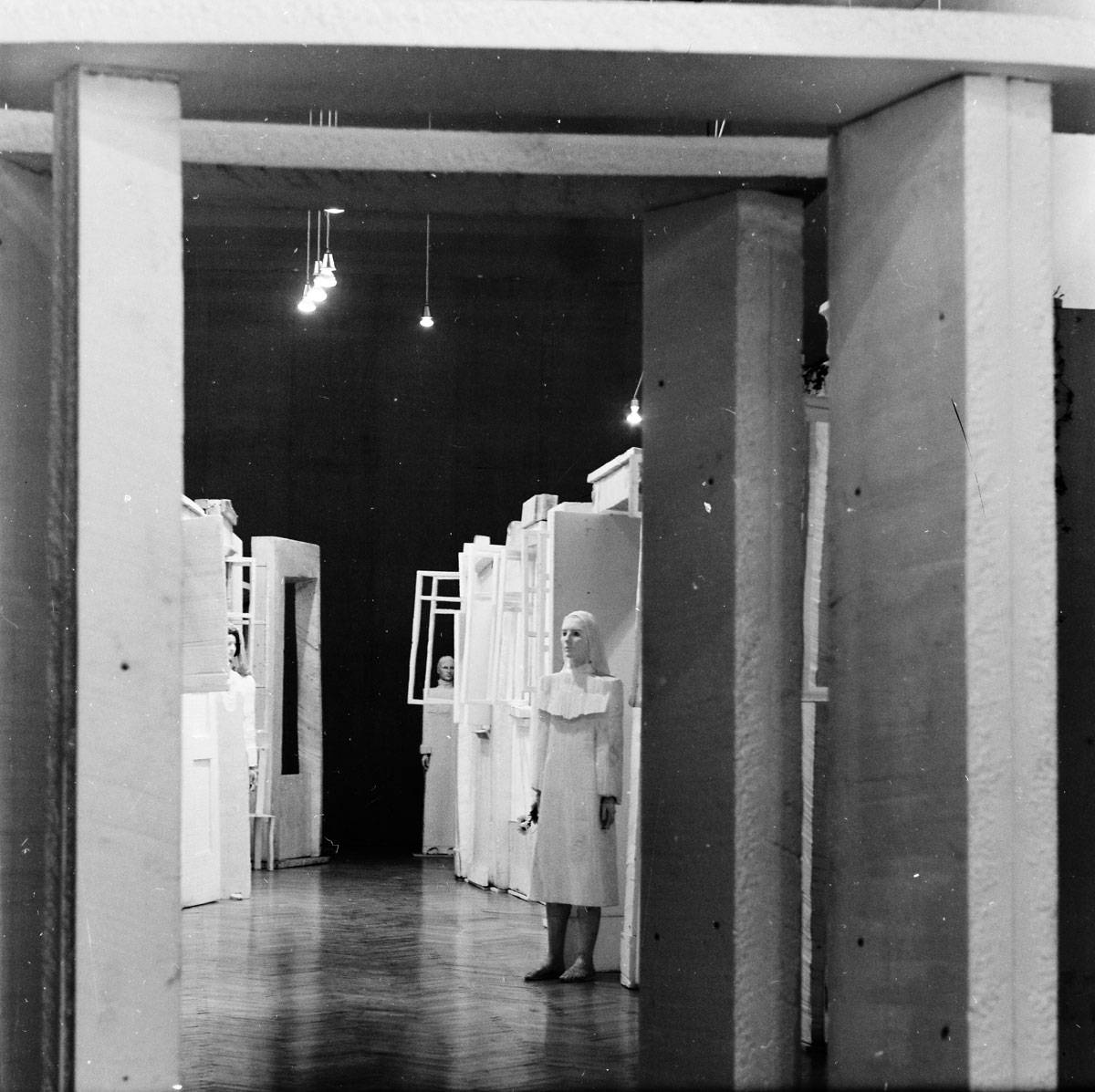

In addition to FMK, the Young Artists’ Studio (FKSE), founded in 1958, was the most important organization for artists at the beginning of their career. The studio primarily helped fresh college graduates through scholarships, studio use, and by providing exhibition opportunities. The organization’s own exhibition space, the Stúdió Gallery, opened in the summer of 1972 at 52 Bajcsy-Zsilinszky Road. Prior to this, members were only rarely able to arrange a solo exhibition through the Studio, so the association’s management applied to the State Arts Fund (Művészeti Alap) to provide them with their own exhibition space. The unsupported avant-garde artists of the era were also exhibited in the István Csók Gallery in Székesfehérvár several times. As a culmination of her entire oeuvre, for instance, one of the most talented sculptors of the time Erzsébet Schaár composed a large-scale environment, entitled Street (Utca), for the upstairs space of the gallery in 1974. The exhibition was opened by poet János Pilinszky with his poems written for the occasion. The most exciting places during this period were the Bercsényi Street Dormitory of the Faculty of Architecture of the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, the Ganz Mávag Community Center, and the Béla Balázs Studio.

Istvan Csok Gallery, 1974

Outside these exhibition spaces in Budapest, members of the avant-garde art scene could organize their exhibitions in the ceremonial halls of culture houses or exhibition spaces in the countryside, but most often they were held in the artists’ own studio. This is where the concept of “the second public” comes from, as the works of countless artists could not reach the general, wider public; they could only be presented semi-officially, to a smaller audience. Of course, the concept of the second public is often very problematic, as the formal and informal art scene intertwined many times and in many ways. The prohibition of the works of certain artists was at times completely illogical and inconsistent, since it also depended heavily on the arbitrary decision of the government official in action.

Open only for a few days in 1968 and 1969, the so-called Iparterv exhibitions have become the eponym for a whole generation of artists. The tragicomic nature of cultural politics is marked by the fact that this progressive exhibition was stuck in the hall of a construction company headquarters, hence their name (Iparterv is short for Ipari Épülettervező Vállalat, i. e. Industrial Building Design Company). A freshly graduated art historian, curator Péter Sinkovits invited eleven young avant-garde artists to the first exhibition, namely Imre Bak, Krisztián Frey, Tamás Hencze, György Jovánovics, Ilona Keserü, Gyula Konkoly, László Lakner, Sándor Molnár, István Nádler, Ludmil Siskov and Endre Tót. The following year, András Baranyay, János Major, László Méhes and Tamás Szentjóby joined the list of artists. Ever since then, these canon-making exhibitions have been present as reference points in Hungarian art history. In February 2019, the Ludwig Museum opened its large-scale exhibition entitled Iparterv 50+ on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the second Iparterv exhibition. The exhibition was accompanied by a number of guided tours, talks and lectures, which were held by members of the Iparterv generation among others.

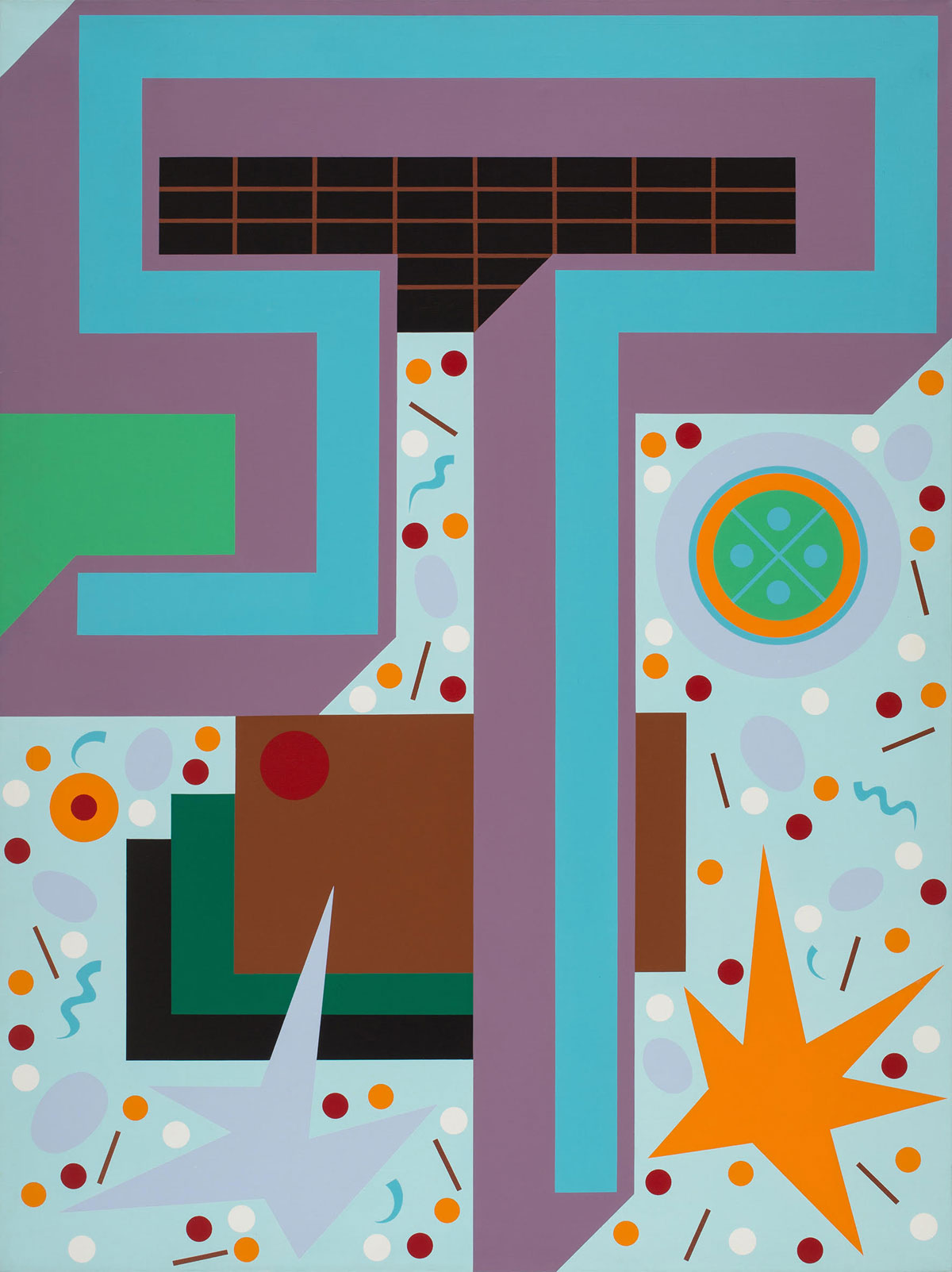

Despite his intellectual greatness, his astonishing versatility and prolificacy as an artist, one of the most vehemently banned artists of the time was Lajos Kassák. A world-renowned representative of historical avant-garde, he did not live to see the Iparterv exhibitions; however, his personality and doctrines have left an enduring imprint on the art world. Kassák was the original leader of Hungarian avant-garde, a multi-talented writer, poet, literary translator and artist. His artistic approach and manifestos have for generations shaped the thinking of Hungarian artists: “We can no longer fit into the traditional limits, either in society or in art. We do not want to compose something new from the old. Our age is the age of constructivists. Art, science, technology come together at one point. The new form is the architecture [architektúra].” The artistic principles introduced by Kassák were revived in the endeavours of New Constructivists. Unique painting techniques have emerged, such as hard edge painting, painting on molded canvas, or the deconstruction of traditional panel painting. János Fajó’s vibrant colors, Ilona Keserü’s folk motifs, Imre Bak’s geometric structures, and István Nádler’s lyrical abstraction have evolved around these ideas. The grip of Communism was loosening, and artists were given more and more opportunities to show their works.

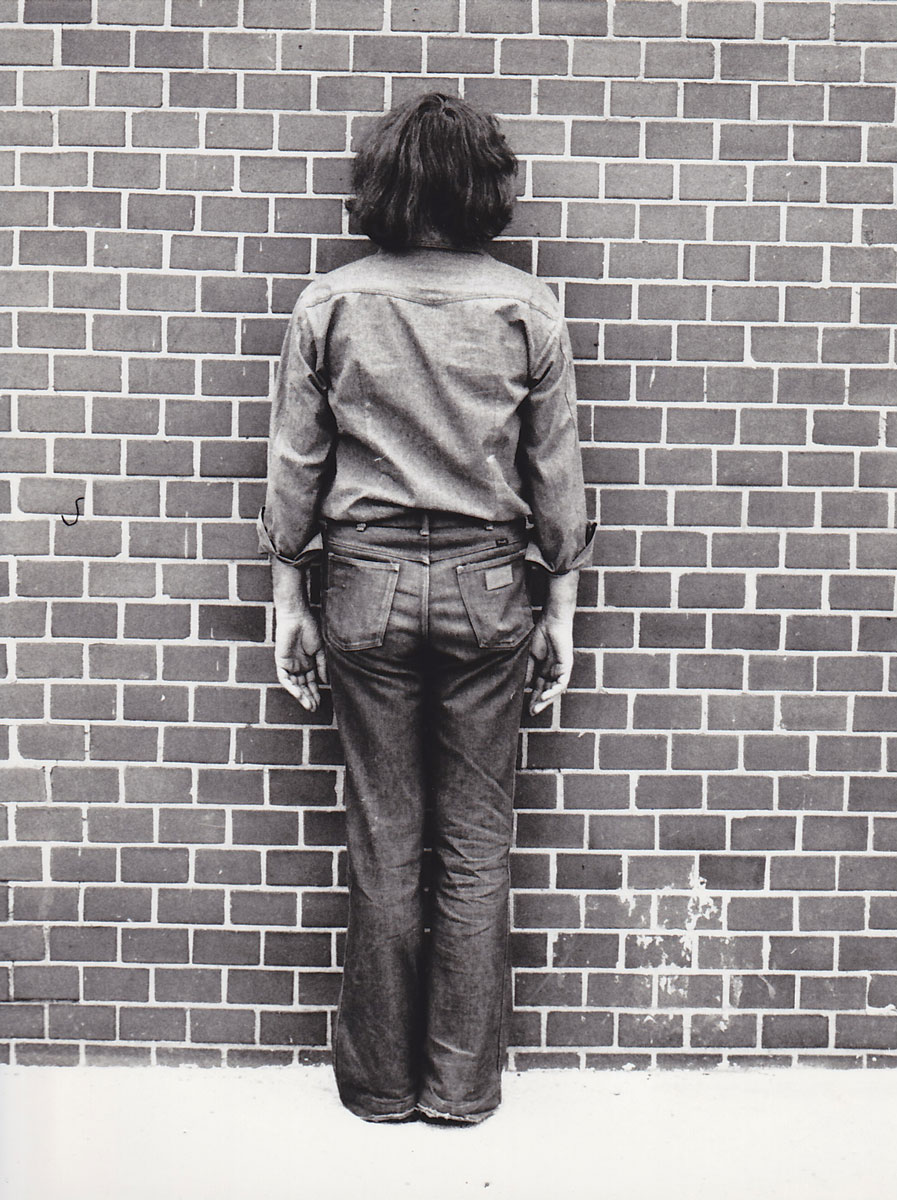

It is here that we have to mention one of the most important movements of the era to which countless great artists were able to connect: concept art (or conceptual art), which opened up whole new perspectives for artists. Instead of the market value of the works of art, total ‘immateriality’ has taken precedence. The spread of conceptualism has brought about a paradigm shift that changed the earlier conception of art. The main figures of conceptualism were Tamás Szentjóby and Miklós Erdély, but a number of artists, including Dóra Maurer and Gyula Pauer, had conceptualist periods in their oeuvres. Conceptualism has emerged in Hungary in the 1960s, reaching its ‘golden age’ in the mid-70s. Its enormous impact is mainly due to the change of attitude that can still be felt in the works of numerous artists. Sometimes directly, sometimes more indirectly, but it had a great influence on the works of Emese Benczúr, Balázs Beöthy, Antal Lakner, Attila Menesi, Gyula Várnai, Pál Gerber, Gábor Gerhes, Szilvia Seres and János Sugár.

1975, silver gelatin print, 11,9 x 9 cm

One of the most prominent informal art venues of the time, was the Chapel Studio in Balatonboglár (Balatonboglári Kápolnaműterem). After finding the abandoned chapel, painter György Galántai decided to found an exhibition space that would house progressive exhibitions that were often banned in Budapest. He rented the chapel for fifteen years from the Catholic Church. Following a series of lengthy bureaucratic procedures, the first exhibition opened in 1970. Over time, “traditional” exhibitions originally falling into the ‘tolerated’ category, were gradually replaced by increasingly progressive ones featuring actionist and performative events experimenting with various media, as well as projects expressing criticism of the current institutional and political system. The Chapel Studio soon became the most important meeting and creative base of neo-avant-garde art; in addition to Hungarian artists, it also had a significant number of international guests. Various experimental art events were held over three summers: the venue hosted Dóra Maurer’s poetry presentation, Péter Halász’s theatre productions, László Beke’s lectures and Tamás Szentjóby’s happenings. The ever-suspicious, often “unmanageable” events and exhibitions did not go unnoticed by cultural politics. At first, they tried to undermine the activities, then in August 1973, the lease for the chapel was terminated and Galántai, who was living there at the time, was evicted.

The government has made it difficult for artists to emerge and to thrive, but politics have also greatly contributed to catalyzing modern art trends. Artists were united in their stand against official directives as well as the desire to find new ways of artistic creation. The emerging genre of mail art at that time provided an opportunity for international connections. A new kind of interdisciplinarity was emerging, with strictly defined genres being gradually replaced by a transmedial artistic attitude.

Along with the mixing of genres and the spread of new mediums, the dimensions of painting have also widened. Surnaturalism (a combination of surrealism and naturalism) was replaced by hyperrealism, although that was typical of only a certain period of time for most artists. Hyperrealism appeared primarily in the oeuvres of Tibor Csernus, László Fehér and Ákos Birkás. In the second half of the 1970s, performance art emerged as a continuation of body art and happening. The most notable artist of the genre was Tibor Hajas, whose artistic searchings revolved around the aesthetics of life and death. Hajas, like his contemporaries, experimented in several genres; he primarily considered himself a poet, but it was his performances that made him widely known to posterity. As the desire to capture the unrepeatable moment was always an important goal of his art, his performances were always accompanied by photographic documentation. A recurring elements of these photographs is the flashing light of magnesium or a modern flash. His most common topics were the suffering of the body, self-sacrifice, and the destruction of the ego, an idea borrowed from Eastern philosophy.

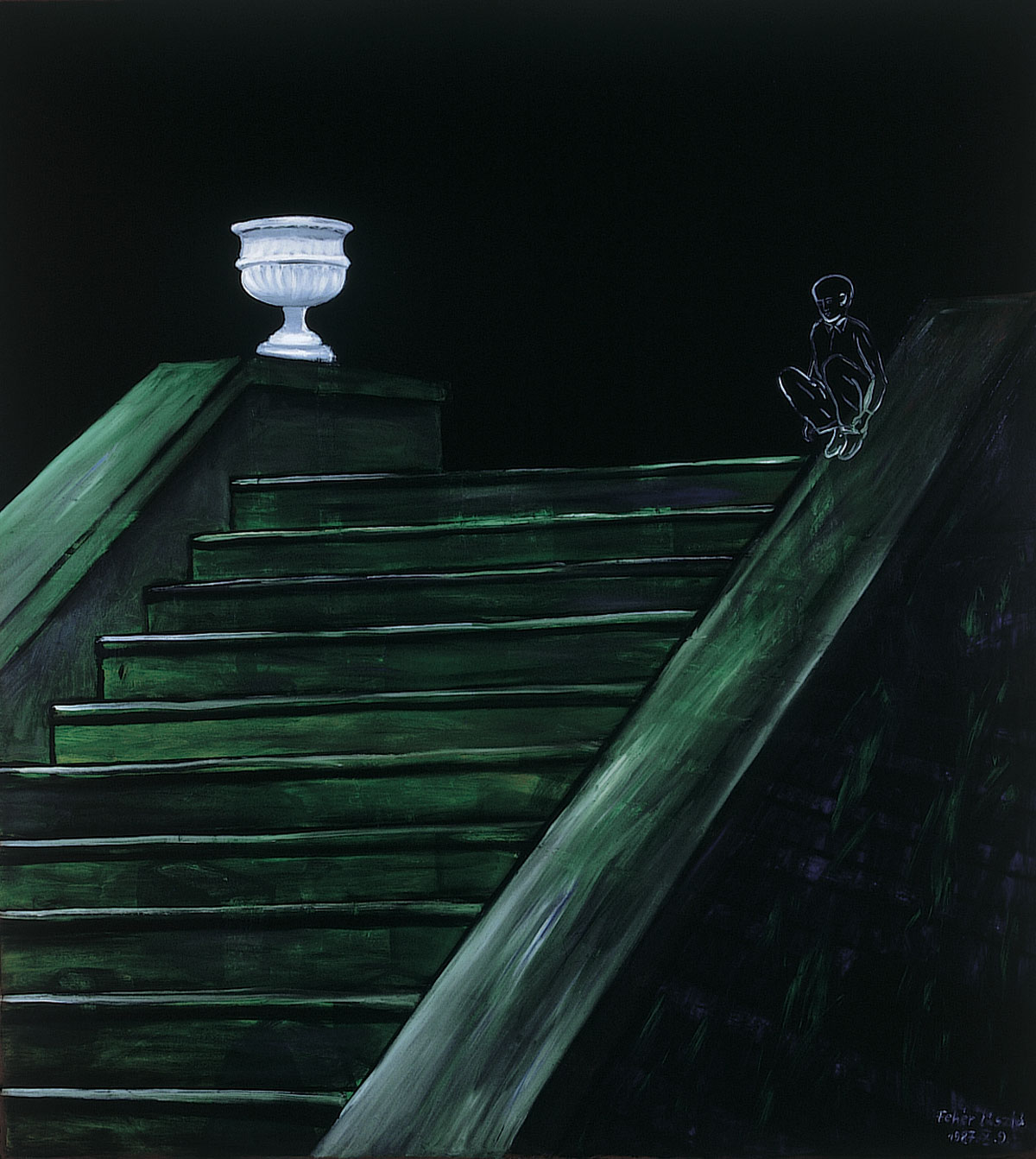

1987, oil in fibreboard, 200 x 180 cm

Photo: Miklós Sulyok

In the eighties, the previous system of values changed considerably. Rejection and overwriting have been replaced by a consistent reassessment of artistic legacies and tradition. Lóránd Hegyi, the most prominent curator and art historian of the period before the regime change, divided this decade into three coexistent trends. The first is individual mythology, the second is new painting or new sensibility, and the third is the post-geometric trend. The constant search for identity, confrontation with cultural history and subjective historism are all the more characteristic of this period. From a formal point of view, pluralism and eclecticism were the most prominent, and were vigorously present until the early nineties. According to Lóránd Hegyi’s typology, the “new sensibility” brought with it much more resigned, introverted, almost sensual works in contrast with avant-garde modernity and conceptualism. Artworks proclaiming the cult of individuality were born, and the members of the group of New Sensitivity had numerous exhibitions both in Hungary and abroad. The exhibition Eklektika (Eclecticism), held in the Hungarian National Gallery in 1986, is of outstanding importance in the context of the Hungarian art scene, since new artistic trends were now allowed to appear in a state institution. It was at this time that a change of attitude has started: the strict opposition to contemporary art began to dissolve. The Knoll Gallery and the TAT Gallery in Vienna exhibited more and more Hungarian artists, and several previously prohibited publications were printed.

The soft dictatorship of the 1980s came to an end, and in 1990 a change of regime took place, which triggered huge changes in society. The Berlin Wall was torn down, Moscow’s central governing power weakened, free elections were called, and the Czech Republic and Slovakia split up. The principle of the three T’s has finally been abolished in the press and in the arts. The precondition for the creation of art projects was not the ideological or political support, but the financial background. State support for art remained, albeit significantly reduced. The distinction between the “first” and “second public” dissolved, and the search for identity began again among Hungarian artists. This particular quest is all the more justified as the opposition to power became obsolete, and new goals and visions had to be found.

Places, missions, opportunities – The venues and the role of contemporary art in Budapest

During the Communist oppression, progressive artists were mostly excluded from state institutions and could exhibit only in the ceremonial halls of cultural houses and their own studios. With the loosening of the system and the softening of dictatorship, the banning of artists have become increasingly rare. In the period immediately following the change of regime, private galleries such as Knoll or Várfok also played an important role in contemporary research: without their work, it would be much more difficult to reconstruct the fine art trends of the 1990s in Hungary.

The change of regime also meant a change for the art scene in the financial sense: although state support for art was reduced, artists could apply for numerous grants, while for-profit galleries also started to flourish. In 2004, Hungary joined the European Union, which also led to newer and easier applications for grants and fellowships as well as residency programs and international cooperations.

Similarly to other countries, the scarcity of public institutions’ annual budget for buying new artworks still does not allow them to provide stable financial support for artists. The canon-making power of the most important state-run institutions of contemporary art in Hungary, the Ludwig Museum, the Hungarian National Gallery, the Capa Center, the Modem in Debrecen, the Budapest Gallery on the domestic scale is indisputable. However, many times politics, the maze of administration and bureaucratic hurdles prevent them from realizing a truly progressive and generous program. In municipal galleries and exhibition spaces artists usually receive little or no financial support for the organization of their exhibitions. Being an artist in the nineties could only be a part-time job – just as it was in the neo-avant-garde. This trend is slightly improving as we are headed towards 2020. The art market is growing considerably, many contemporary artists are supported by the Derkovits Scholarship Program, the Esterházy Art Award, or the collectors of the gallery that represents them. Still, younger artists are often only able to support themselves fully by holding down multiple jobs, which typically includes teaching and applied graphic design jobs. Curator Tamás Don has dealt with the financial difficulties and social image of beginning artists at several exhibitions, such as Time of Our Lives? (Ezek a legszebb éveink?, Modem, 2018) or Therapy (Terápia, Centrális Gallery, 2018). It is indeed a difficult topic, as making a living as a contemporary artist is nowhere near easy. However, this trend is not only true for artists. Most of the theoreticians who leave public institutions find new employment in private galleries. This is partly due to the increasing amount of research and publications financed by for-profit galleries.

Esterházy Privatstiftung, Hungary

Since the millennia, the Western European and American idea of a well-established, accomplished artist’s mindset being much closer to that of a manager or entrepreneur than to a creator quietly working alone in their specific field is not completely foreign to our country either. Today, for-profit galleries in Budapest are the most prominent in the spreading of new trends and the representation of young Hungarian artists abroad. Participation in art fairs abroad, artist exchange programs and increasing sales put Hungarian artists on the map of the international art world.

It is beyond the scope of this article to present a complete list of art venues of the present, but below there is a list of the most remarkable private galleries in Budapest, the must-visit state institutions and the most exciting off-spaces.

There is no doubt that acb Gallery is currently the most successful for-profit contemporary art gallery in Hungary. Acb opened in 2003 to represent neo-avant-garde and contemporary artists in Hungary and abroad. At the start, their resident artists included Imre Bak, Katalin Ladik, Tamás Hencze, Gyula Pauer, Tamás Komoróczky, Marcell Esterházy, Gábor Gerhes, Ferenc Gróf, etc.

exhibiton: There is a hole in the back of my head and I enjoy looking out of it, Budapest, acb Gallery, 2015

Since 2016, the gallery has been organizing exhibitions in three different spaces: the acb Gallery, the acb Attachment, and the acb NA. In addition to the operation of the three exhibition venues, they cooperate with several state art institutions, so they often lend artworks and organize exhibitions at external venues as well. Foreign guest curators and artists are often invited to the exhibition spaces, on the one hand, for the purpose of constantly expanding the circle of acquaintances, and, on the other hand, keeping track of international art paradigms. The owner of the gallery, Gábor Pados is a true trendsetter of the Hungarian art scene. In his view, Hungary would have to overcome provincialism as well as the characteristic depressive attitude in order to have a really successful art scene – and we must admit, he is not wrong. Before the foundation of the gallery, Pados started to become acquainted with Hungarian art due to the influence of his childhood artist friends (later called the Újlak Group) from Szombathely. In 1988, his passion for collecting began by purchasing one of Péter Szarka’s oil paintings, which eventually evolved into a respectable selection called the Irokéz Collection. The current curator of the gallery is Áron Fenyvesi, whose main goals include, in addition to supporting the careers of young artists, exploiting the increased interest in the art trends of the 60s and 70s. Acb’s professional renown has been increasing even more since September 2015 with the establishment of the acb ResearchLab division. ResearchLab focuses on researching, processing and publishing neo-avant-garde and post-avant-garde oeuvres in Hungary in the context of current international discourses.

acb Gallery

One of the oldest for-profit galleries in the country, the Várfok Gallery was founded in 1990 by Károly Szalóky, a charismatic personality of the Hungarian art scene. Located in the neighbourhood of the Buda Castle District, the gallery is divided into two units. In its larger, nearly 300 square meter exhibition space, exhibitions of accomplished contemporary artists are held. From the list of long-time loyal resident artists of the gallery we have to mention Péter Korniss, El Kazovszkij and János Szirtes, who probably had/have the greatest impact on the younger generations. The Project Room, located on the other side of the street, specifically features emerging artists, such as Máté Orr, known for his fascinating figurative paintings, László Győrffy, famous for his horror-inducing paintings and objects, or Roland Kazi, an intermedia artist who explores human perception and identity.

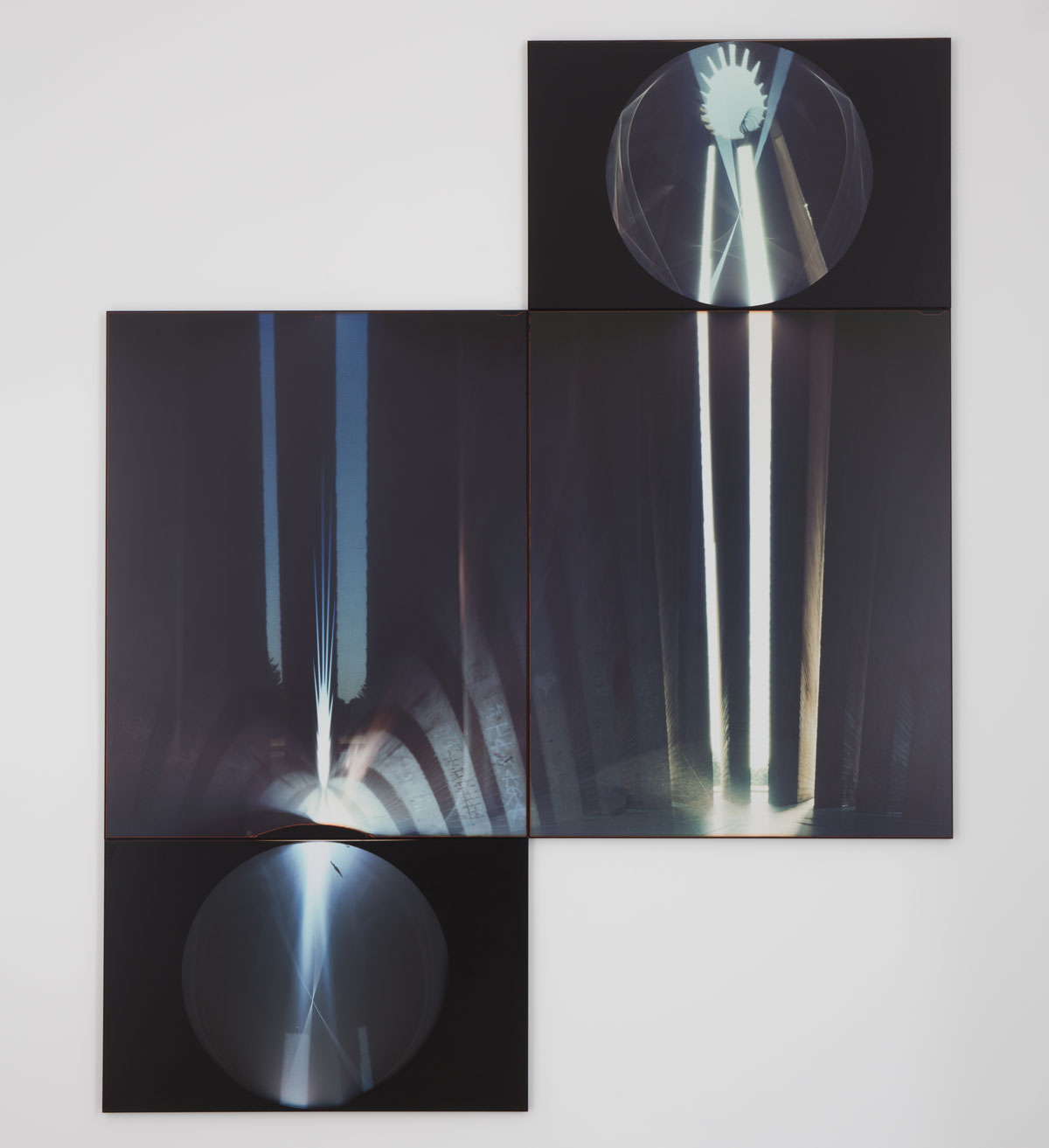

Another notable commercial gallery in the capital is the Vintage Gallery, which is located next to the Károlyi Garden. Opened in 1996, their mission is to represent Hungarian modern and contemporary art both in Hungary and abroad. As photography inhibits an especially significant place in their portfolio, they have been exhibitors at the Paris Photo Fair from the 1990s to the present. Although, most of the contemporary artists associated with the Vintage Gallery cannot be called photographers per se, photography is widely represented in the majority of their artists’ oeuvres. The owner of the gallery, Attila Pőcze, started his career at the Mai Manó House of Hungarian Photography and opened his own gallery a few years later. The Vintage Gallery covers three topics: modern Hungarian photography between the two World Wars, conceptual art from the 1960s to the change of regime, and contemporary art. Their team of artists includes, among others, Miklós Erdély, Kamilla Szíj, Gábor Ősz, Tibor Gáyor, Andreas Fogarasi, Vera Molnár, Péter Türk, and Dóra Maurer, an outstanding figure of Hungarian fine arts, whose solo exhibition opened at Tate Modern in London in the fall of 2019.

2019, Installation view of Dóra Maurer at Tate Modern

Photo: Tate Photography (Matt Greenwood)

The Vintage Gallery also represents artists experimenting with new media (e. g. Gábor Ősz). An important part of the Gallery’s operation is the publication of books and various publications, which not only “extend” the duration of exhibitions, but also generate contact and new context for them.

2017, arcival pigment print, 196x248cm, ed3+1

courtesy of Vintage Galéria

Perhaps the most professional in managing international presence, the Molnár Ani Gallery is also a significant point of reference in the Hungarian scene. The gallery mainly deals with installations, sculptures and paintings, but also shows great openness to transmedial arts. Integrating Hungarian art into the international scene was an important goal for them from the beginning. Economist Annamária Molnár, the owner of the gallery, has been selecting fine art pieces with impeccable taste for eleven years now. The list of exhibited artists include emerging artists like Sári Ember, Balázs Csizik or Dániel Bernáth; Emese Benczúr, Ottó Vincze and Ekaterina Shapiro-Obermair represent the middle generation, István Haász and Tamás Waliczky the older generation. Indeed, the experiences of gallerists show that survival in the international contemporary art market is only possible with an international team of artists and by cooperating with foreign galleries.

Gallery owner Erika Deák also attaches great importance to the creation and maintenance of international discourse. One of the prominent artist of her gallery, Attila Szűcs was contacted by the Federico Luger Gallery in Milan thanks to several years of fruitful cooperation. The Erika Deák Gallery was established in 1998 and has been an important part of the contemporary art scene in Budapest ever since. Since 2014, Zita Sárvári has been in charge of foreign relations and the development of the gallery’s artistic profile. Erika Deák has attached great importance to mediation between the public and contemporary art from the beginning. In her view, the task of a gallery is to create a milieu that anyone can enter, and in which a connection between the viewer and the exhibition is born. In addition to his for-profit activities, Erika Deák participated in the Bátor Tábor Charity Auction for many years.

Erika Deák Gallery, 2019

Photo: David Biro

Starting her career at the prestigious Knoll Gallery, Margit Valkó founded the Kisterem Gallery in 2006. She built up the small-sized commercial gallery patiently and very consciously, knowing that the vast majority of Hungarian art collectors were not used to consuming experimental contemporary art. Almost immediately after its establishment, Kisterem started to participate in art fairs. Since then they have appeared on Frieze, Liste and FIAC, several times as the only Hungarian gallery. Breaking into the international art scene and participating in fairs, however, is extremely costly and, in the short term, often quite unprofitable, but both the gallery and the exhibited artist(s) are propelled into a higher category after appearing at a high-profile fair like Frieze London. Getting into fairs is also made more difficult by the fact that Eastern European countries do not have a competitive class of buyers, therefore, many aspiring artists have to work harder to get into the professional scene than the already established artists whose works are already popular among collectors. Nevertheless, Hungarian artists are able to attend world-class fairs more and more often, moreover, with great success, such as Zsófia Keresztes as last year’s Liste.

Former director of the Ludwig Museum, Barnabás Bencsik, wandered into “uncharted territory” in 2017 – and what a great decision he made! Together with Tünde Csörgő, they founded the Glassyard Gallery, which in my opinion is one of the most progressive galleries in Budapest. Their artists have been selected with great taste, the quality of the exhibitions is quite balanced, while their narrative is relevant and visually striking. Among the contracted artists is the Lőrinc Borsos artist duo, known for their interdisciplinary work; Péter Puklus, who connects different mediums; Áron Kútvölgyi-Szabó, who deals with cognitive distortions and fake news; Antal Lakner, initially a member of the post-conceptualist generation; Szilvia Bolla, who is playing with the nature of light; and Attila Csörgő, who explores human perception. Each and every one of them create unusual, often surprising intermediary works, and are of prominent international importance. We hope that the gallery’s initial breakthrough successes will continue.

2019, Glassyard Gallery

photo by Dávid Biro

Basically, every artist expects their gallerist to promote them, to connect them with foreign galleries, and provide them an opportunity to introduce themselves, so they can be discovered more quickly by both art professionals and collectors. For this reason, the majority of private galleries now strive to collaborate with several foreign artists to facilitate networking and cross-border discourse. Hungarian artists also need to see where the various creative trends are going abroad to be able to reflect on global issues as well as to examine their own situation and themes from different angles. In addition to their for-profit activities, the galleries mentioned above undertake a cultural mission. However, there are also spaces that, due to their dominantly unique profile, become refreshing spots of the scene. From the Budapest art scene, I would like to mention the outstanding feminist project gallery called FERi. Led by art historian and curator Kata Oltai, this project space hosts extremely important art and community events. Talks, visual festivals, lectures, film screenings, exhibition openings and finissages, and even theses consultations, all connected to women’s perspectives and gender studies, are happening here. The gallery also cooperates with foreign guest curators and artists, breaking open and reinterpreting the strict boundaries of art exhibition to engage in dialogue on important social issues. I would like to hope that more and more similar initiatives will be launched in Budapest in the future.

The idea of a large-scale, privately-owned, multifunctional arts centre in Europe has long been widespread; in Hungary, it is just beginning to take root. Located in the buildings of the old Haggenmacher Brewery, the place closest to this model is Art Quarter Budapest, one of my favourite off-spaces. It is true that it is located on the edge of the city, but what happens here always draws you out of your entrenched ways of thinking and from the anxieties of everyday life, which is especially uplifting. The huge brewery building offers plenty of opportunities for creative activity. In addition to contemporary art exhibitions, there are theatre and circus performances as well as concerts, conferences and other events. They also host a residency program and, not surprisingly, a studio. The spaces have been beautifully renovated, yet retain the ancient atmosphere of the place. Since its opening in 2015, the aqb Project Space has hosted many great projects both from Hungary and abroad.

aqb Project Space, 2018

Photo: Áron Wéber

Another large off-space is the Artkartell Project Space. Located in the former industrial site of the PP Center and spreading 45,000 square meters, its exhibitions are curated by Gábor Rieder in collaboration with Marcell Pátkai.

Among the institutions with a foundation as their background, the favourite refuge of many is the House of Hungarian Photographers in Nagymező Street, or as everyone calls it, the Mai Manó House. Built at the end of the 19th century, the magical studio house is the intellectual and professional centre of Hungarian photography. Primarily serving as an exhibition space, its objective is to introduce both classic and contemporary representatives of Hungarian and international photography to the Hungarian audience. In addition, they regularly organize conferences, guided tours, book and catalogue launches. It is worth checking out their tiny but immensely rich bookstore, where sometimes you can even buy unique numbered photographic publications. Thanks to Mai Manó House’s professional embeddedness, they have been assisting the artistic, scientific and cultural activities of photography since 1995 as well as highlighting the professional and social status and role of Hungarian photography.

photo: Imre Kiss (Mai Manó Ház)

Photo: Imre Kiss (Mai Manó Ház)

Across the street from Mai Manó House there is the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center, housed in the former Ernst Museum. Launched in 2013, the institution has been the leading visual centre in the country ever since. Thanks to its fresh-faced curatorial staff, the Capa Centre’s exhibitions always provide a relevant and straightforward approach to global and local art issues.

A short distance from the city centre, there is the Ludwig Museum, Hungary’s premier contemporary art institution, which can be reached by a pleasant journey by tram along the Danube quay. The museum was founded by Irene and Peter Ludwig, a German collector couple in 1989, and is currently directed by Dr. Júlia Fabényi. In addition to promoting contemporary art, Ludwig is engaged in a significant community building activity, with a particular focus on social responsibility. Instead of hosting travelling exhibitions, they organize their exhibitions with in-house own curators, focusing on the domestic audience. From 2015, the Ludwig Museum organizes both the art and architecture exhibitions of the Hungarian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

The main task of the Hungarian National Gallery, located in the Buda Castle, is to present Hungarian art from the Middle Ages to the 20th century, but its profile also includes contemporary art. The leader of the contemporary collection, Zsolt Petrányi, and his team are organizing outstanding exhibitions that are worth paying attention to.

The Hungarian contemporary art scene is becoming increasingly diverse and internationally acclaimed, to the delight of audiences and professionals alike. Many new art institutions and exhibitions will open in the near future, which we hope will expand the scope of domestic art and launch further international co-operations.