Gerda Széplaky

Individual mythologies

Post-feminism in contemporary Hungarian art

Introduction

The history of feminism dates back at least a century, provided that we consider the initial (if not the very first) period of emancipation and the fight for women’s rights. Ales, it is advisable to do so because with the establishment of the first women’s movements, women’s painting schools opened all over Europe, including Hungary: women as artists became part of the fine arts discourse from that time on. However, in the strict sense, we can only speak of feminist art from the second wave of feminism, stemming from the activities of the movements that followed after 1968. By this time, women are no longer interested in pursuing equality, they are not driven by a “desire for identification” with men, but on the contrary, they are motivated by differences. They attempt to define gender and social roles along a construct of feminine identity that is based on a specific world experience of women. Thus the focus is shifted to the issues of identity, a different kind of perception and understanding of reality, a unique way of exploring the meaning of signs, and the possibilities of the symbolic realizations of femininity. It is during this period that radical feminism emerges, blaming heterosexual culture and gender stereotypes for women’s subjugation. The third wave of feminism, defined here as post-feminism, begins in the 1990s. The term post-feminism is linked to postmodern theories, first and foremost the theory of Julia Kristeva, a “student” of Lacan, according to which the essence of our being is no longer defined by gender differences, but by duality: feminine and masculine ways of experiencing the world are both parts of human identity. Judith Butler shifts this assertion somewhat toward a performative identity policy by denying the essential reasons behind female attributes, moreover, she deconstructs the “feminine” by referring to a diversity of experiences, not feminine and masculine. Butler, both in the case of femininity and masculinity, argues that gender identity is a performative accomplishment. Amy Allen sees the acceptance of a feminine identity neither as a biological issue, nor as identification with women with similar characteristics to us, but as a political fact. From this, Amalia Sa’ar derives an identification policy that considers femininity not as determinative or essentialist, but as a “free choice”. Post-feminism, in addition to seeing women’s emancipation struggles complete and finished, is based on this freedom. In this article, I present post-feminist artistic endeavours in Hungary.

The post-socialist discourse

During the time of socialism in Hungary (similarly to other Eastern European countries) feminism was based on the logic of sameness, which has promoted gender equality through equal participation in labour, and has put in place countless measures in favour of working women. Top-down feminism, however, did not simply proclaim the elimination of sex differences, rather it made impossible the true representation of femininity. Women could become “equal people”, but they were neither allowed to criticize the dominating patriarchal system of values, nor to act radically. As a result, post-feminist art took on a unique form: it was a culmination of both the missing second wave of feminism and the third wave that had already transcended the critical attitude towards patriarchal culture. In post-socialist discourse, a distinctive “mixed” post-feminism emerged, in which both the critical voice and the liberation stemming from the diversity of identity were present.

The feminism that emerged in Hungary after the change of regime can be called “shy feminism”. Hungarian women now considered feminist achievements (such as the right to study, to work, to have control over their own bodies) to be natural, yet they were afraid to proclaim themselves to be feminists. All this resulted in “weak feminism”, though this can only be seen in the reception of feminist art. However, the artworks themselves were characterized by a frivolous and ironic tone rather than shyness or weakness, while at the same time displaying the ease and naturalness of the choice of identity.

Before 1989, there was virtually no “women’s art” in Hungary. Following the change of regime, there was a proliferation of works expressing an intent to define gender identity, albeit initially in a veiled, “disguised” manner, which can be explained by the lack of feminist philosophical background at that time. It was a great change from the male-dominated art canon of the 1980s, when women artists were finally given opportunities to appear in state representation: one of the best examples is the 1997 Venice Biennale, where Hungary was represented by Róza El-Hassan, Judit Herskó and Éva Köves. More and more historical and thematic women’s art exhibitions were opened, which now focused on the issues of gender roles and the characteristics of language use, as well as the gender-specific ways of experience and expression.

In 1995, the first series of exhibitions entitled Water Ordeal was launched at the Óbudai Társaskör Gallery (curated by Gábor Andrási), which specifically featured women artists, including Ilona Lovas, Mariann Imre, Ágnes Deli and Mária Chilf. At the turn of the millennium, the exhibition entitled The Second Sex opened at the Ernst Museum (curated by Katalin Keserü). Using both historical and thematic grouping, divided by genres and media, its aim was to provide an overview of Hungarian women’s art from 1960 to 2000. It was especially revelatory that women artists whose works were known already but had never been analyzed with a feminist approach before, such as Margit Anna, Dóra Maurer and Ilona Keserü, were also included in the discourse. In this new light, it became evident that works that were previously interpreted as part of the reigning patriarchal canon, were actually taking a stand against it, such as the knitted Sentry Box (1976) by Zsuzsa Szenes, or Preserve (1976) by Gizella Solti. However, some of the defining personalities of Hungarian feminism have been omitted from the exhibition.

By the end of the 20th century, a feminist discourse has emerged in Hungary that focuses on the representation of femininity, while also representing a wide range of attitudes, not only regarding artistic expression (i. e. various media and techniques), but also the diverse forms of identity. Since 2016, the contemporary women’s art scene also has its “own” platform of representation called FERi, a non-profit, feminist gallery owned and run by art historian Kata Oltai.

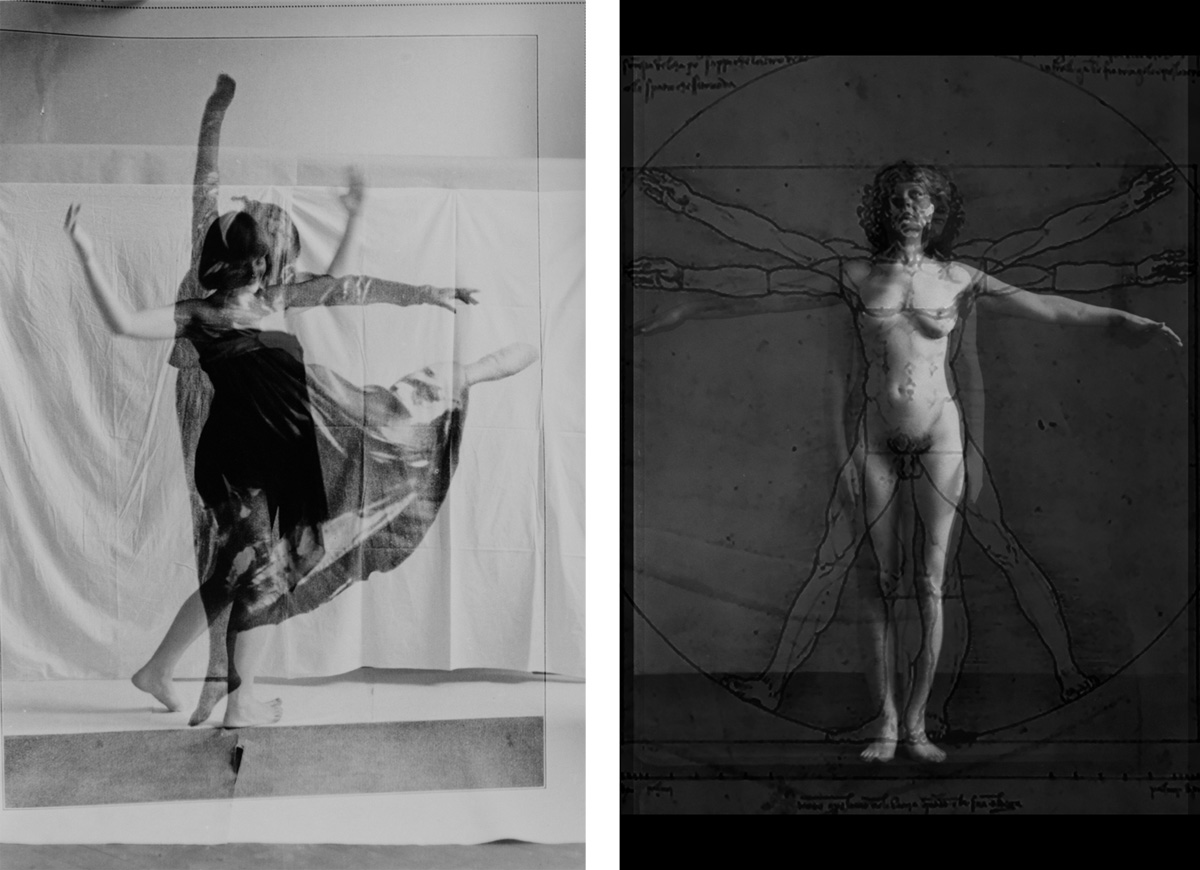

Orsolya Drozdik (Orshi) influenced Hungarian post-feminist discourse not only with her works, but also with her collection of feminist essays, entitled Walking Brains (1999), which played a huge role in shaping the theoretical background. For a long time, Drozdik was the only one in the Hungarian scene who, returning home after a long stay in New York, represented a post-feminist attitude: she no longer intended to determine a woman’s place along the lines of a critical attitude, that is, in relation to masculine forms of identity, rather she was solely concerned with her own self-representation. From the outset, Drozdik’s art revolved around understanding, creating and presenting the self. She started her career in Budapest, then moved to Amsterdam in 1978 and then to New York in 1980. In the period before 1978, as an artist living beyond the Iron Curtain, it is understandable that her feminism has shifted towards radicalism. After all, it was the unequal gender roles, the application of double standards, and the discourse defined by patriarchal values that prompted the development of a form of identity in which being a woman and being an artist were equally important. The neo-avant-garde forms of expression emerging at that time proved to be a suitable tool for formulating radical (not frivolous, but subversive) questions about the traditional artistic canon and women’s empowerment.

In her series of performances and photographs entitled Individual Mythology (1975–77) and Free Dance (1975–76), she reflected on the issues of identity models available to women artists by taking on the role of dancers.2.

Being a dancer involves experiencing the liberating act of physical existence. During the performances, Drozdik projected photos of dancers on her body while dancing, thus transforming herself into the experience of a free state of the body. She started collecting nineteenth-century photographs of nude figures and models for her series NudeModel (1975-77). She developed her own system and terminology for collection and reuse, called the Image(Imago)Bank theory (1977), based on which she started using a combination of different techniques as her work method. It was important for her in the intermedial works she created in this period for the idea and the concept behind the work to be emphasized, and not the medium or the way of execution. Conceptual art as a work method helped her to “subvert” traditional art and create a place for the individual mythology of the woman, which she could only do within the criticism of the dominant discourse (and not outside of it).

In order to create a new mythology that positions the woman artist against the “disciplining and coercive” powers of art historical canon, she had to construct a new (feminine) concept of self. Drozdik had to create the “replayed self” in the artistic discourse of the socialist culture of the seventies, in which figurative representation with an academic-humanist perspective coincided with the censored Marxist-Leninist way of portrayal. For the construction of the aforementioned self, she was offered two patterns at the same time: one of them was women represented by art history, that is, the objectified female body depicted as a nude, while the other was the woman who identifies as an artist, with a conscious sense of self. All this resulted in dual self-portraits and self-nudes: when she portrayed the body as an artist’s, she looked at it with the cold gaze of the viewer, but when she offered her body as a model’s, she simultaneously experienced – from within – her own objectification, vulnerability, and desire.

In the nineties, now in New York, as feminist theories made her more conscious of her femininity and gender roles, the creation of the Self became an even more determined program in her art. The parts of her series Manufacturing the Self (e. g. Body Self, 1983-94; Medical Erotic, 1993; Nineteenth Century Self, 1993; The None-Self, 1993; The Hairy Virgin, 1994, etc.) all deal with different aspects of identity acquisition.

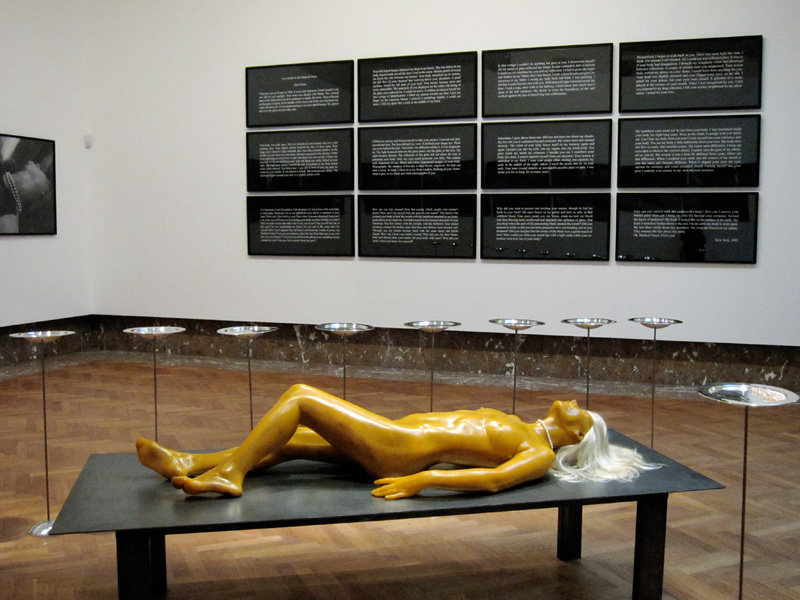

At the centre of her endeavours stands the body model offered by the Medical Venus, created after Clemente Susini’s 18th-century Medical Venus, in relation to which she can assume a feminine identity. Becoming widespread around the world over the centuries, she first photographed a rubber copy of the sculpture at the Museum of the Semmelweis Medical University in 1977. In the 1980s, she also took a series of photographs of Medical Venus statues in medical museums around Europe and America. Medical exhibitions made her realize that tradition has always forced women in all of the patriarchal discourses to assume a dual attitude and experience, and only through reflecting to that can a feminine identity be created. Women are simultaneously motivated by scientific narratives to have an objectifying, analyzing gaze as well as erotic feelings: the female rubber sculpture arouses desire through eroticization. Her installations were accompanied by “love letters” in which she expressed her erotic feelings.

In the installation Body-Self, the life-size rubber casting of the artist’s naked body lies on a metal table in the centre. Next to it are the “love letters” engraved on twelve silver plates, and on the wall are a series of twelve black and white photographs of the Medical Venus which were taken between 1984 to 1993. Texts of different structure and content shed light on the erotic and power relations of medicine. The photos are documents of a historical-scientific narrative: the plastic object is the embodiment of a vulnerable woman, represented only by its anatomy, while the texts placed on cold metal objects (in the place of organs) express the desires of a real-life woman.

The three contexts and sets of objects create the erotic-tuned discourse in which patriarchal (not just medical) culture is deconstructed. Even if it appears more tamed later, this gesture of deconstruction is present in every single one of Drozdik’s work, even those in which the artist is no longer concerned with the social status, the historical or scientific context of the woman, but the experience and representation of the female body from within.

Drozdik thus brought this consistent art program and the freshness of international post-feminist art when she returned to the post-socialist art scene. Her works had (and still have) a crucial influence, and without her, perhaps another kind of artistic discourse, a truly “shy” post-socialist feminism would have taken place. After the change of regime, Hungarian women artists began to develop a program of search for identity, as part of which they sought new expressions: new mediums, new techniques, even new types of artworks and new genres.

Post-feminist aspirations

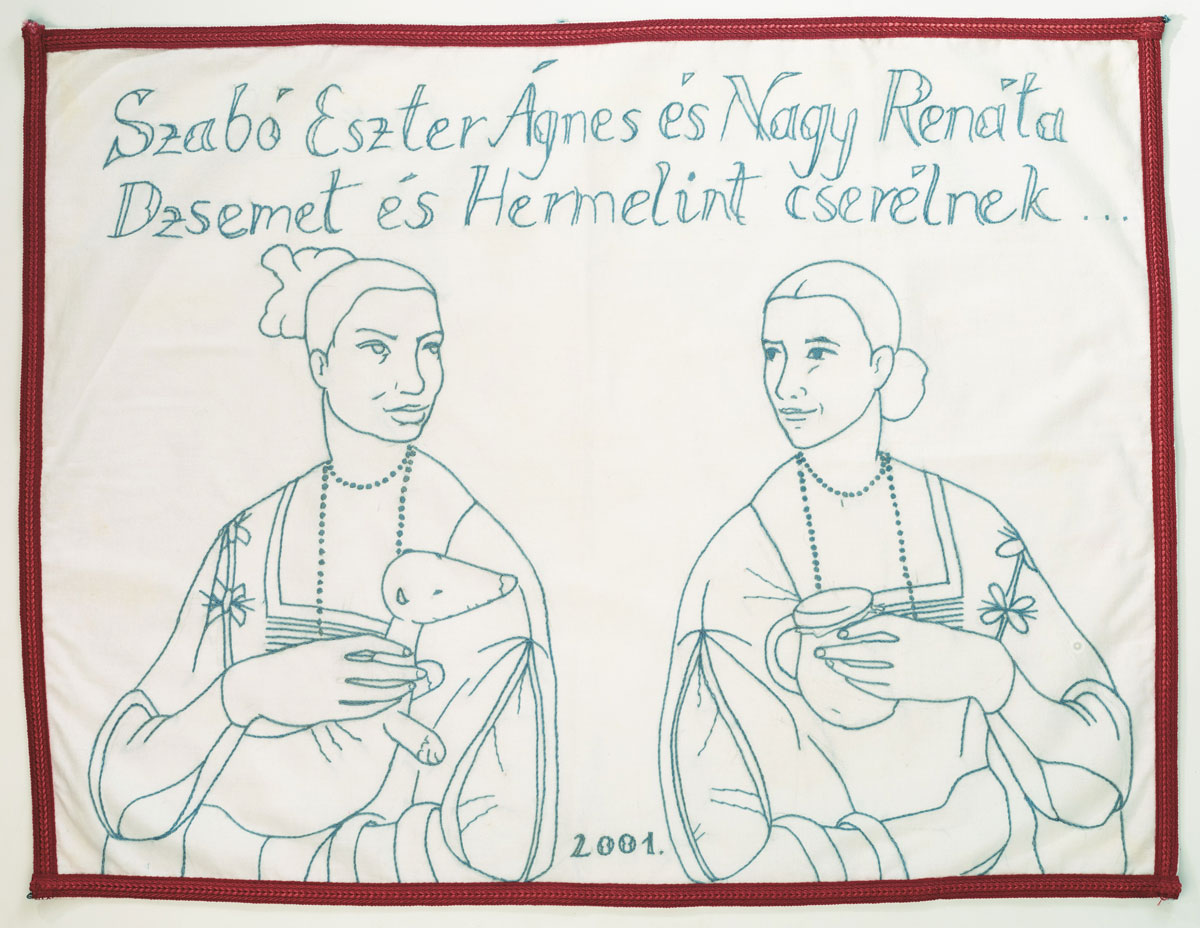

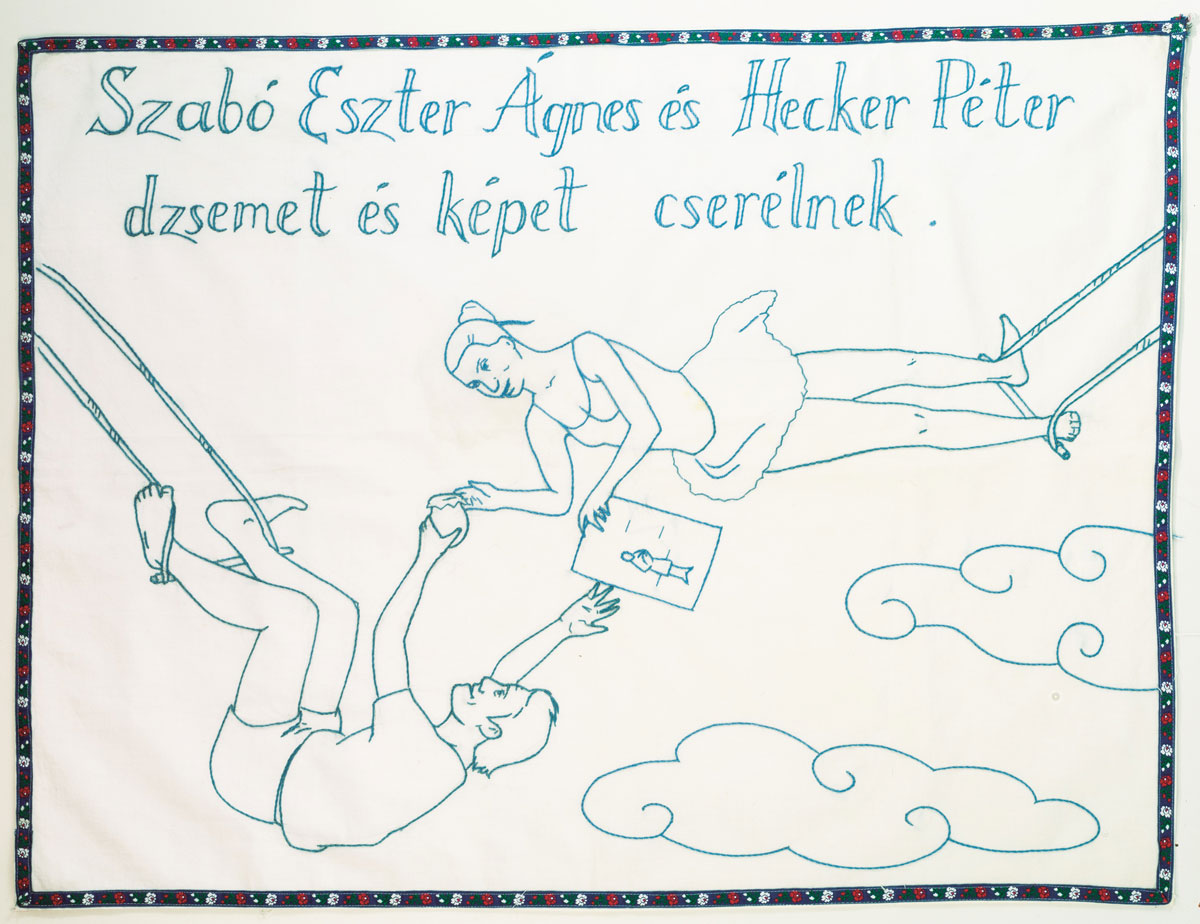

In Hungarian fine art, embroidered images represented a new genre that features the most common use of materials and a form of activity considered to be traditionally feminine, while expanding the closed circle of traditional art forms.

(1999) Bartók 32 Gallery, Photo: Miklós Sulyok

Emese Benczúr’s conceptualist works consistently formulate a verbal message that questions the rationality-based techniques of patriarchal culture as well as the practices of traditionally masculine activities that are thought of as superior. Examples of such “silly messages of women” include Today I Didn’t Go To The Beach Either (1994) or I Fulfill My Duty (1995), in which the meanings of expectations towards women as well their subordinate and hierarchical status are encoded. In Benczúr’s installations, instead of the serious materiality of earlier sculptural approaches, the emphasis shifts to the frailness of the thread, to which she even reflects in one of her embroideries: “[W]here it all hangs by a thread.”

Eszter Ágnes Szabó also does embroidery: her wall hangings ironically evoke Hungarian peasant culture. The embroidered sentences paraphrase folk wisdom while exposing decoded gender stereotypes. An installation including actual jam and marmalade, the embroidered wall hanging in Szabó’s Traffic Jam (1999) features a visual-verbal narrative of how a woman attempts to incorporate her everyday activities, which are mostly considered futile, as valuable into a masculine culture. The image tells the story of the woman (a housewife) who initiates a trade with the man (an artist): for the drawings of Péter Hecker , Eszter Ágnes Szabó gives jam in return. The result of feminine work thus becomes equal with art.

Embroidery is a basic form of artistic expression for Mariann Imre as well. Completing the ethos of Kristeva, her embroidered pieces made of concrete combine masculine material with the subtlety of feminine perception: light threads penetrate cold, hard, grey stones. In her installation of concrete hearts, the red threads that emerge from the inside of the concrete pieces remind us of tiny blood vessels, thus referring to the reality of bloody tissues and organs, the human (not just the female but also the male) body exposed to transience.

Ágnes Németh took a somewhat separate road from the discourse above, as she describes gender identity as a revelation of direct female experience and existence. She also uses rural materials of the “feminine” character, such as cane, bamboo, horsehair, wire braid, or mud; for her, turning to these natural materials means entering into the physical-organic world. Her attitude evokes the art of Ana Mendieta, who, as a feminist representative of nature art, also questions the connections between femininity, physicality and nature. One of Németh’s most important works is Self-bridling (2005), an installation presented at the Bartók Gallery in Budapest. Straw bales, which were carried into the gallery and placed in columns next to the walls, transformed it into a sacred space, the temple of nature.

(2006, photo manipulation serie, 50×70 cm)

Photos by: Szabolcs Králl

At the same time, the good-smelling straw structure made of a “living” material evoked the cozy, warm spaces of femininity. In the performance related to the installation, the artist presented herself as “self-bridled”: she curbed her own savagery, thus articulating that a woman exposed to her physicality could only obey the demands of the patriarchal society if she suppressed her instincts (“Put the bridle in your mouth and discipline yourself!”). In the “stall temple” the horse is symbolically present: as a strong-willed woman seeking dominance, who must be broken as a wild mare; more specifically, if she wants to become part of culture, she must break herself.

(2014, installation, 40x45x280 cm)

In Body Pipe (2014), Németh evokes the image of birth. The piece consists of a so-called varsa, a traditional fish-trap made of willow branches that the artist, in this case, covered in different coloured patches of soil into which she mixed seeds and peat, and glued figures of bronze soldiers in firing position onto random spots on the outer surface of the statue. The whole construction carries a strong formal resemblance to the womb, and this is made even more evident by the installation inside: a holed-out rectangular shape made of dirty medical gloves can be recognized at the bottom of the varsa, directly on the ground. In this way, the work presents the womb as a hollow, oppressive space that does not accommodate life and birth, but excision, autopsy, and death. The Body Pipe can also be interpreted as a spatial-visual parable of abortion, that also provides a philosophical reading of the work, which is that patriarchal culture, through its nature-oppressing (medical-scientific) practices, extracts from the woman her sensuality, thereby eradicating her true power, her fertility.

1997, Installation, 72 x 112 x 112 cm

Metal contruction, velvet, rabbit skins, moss

Photo: Marián Ravasz

This medical-scientific context also provides the background for Ilona Németh’s installation Private Clinic (the work implicitly refers to Orsolya Drozdik’s Medical Venus pieces). The installation, which focuses on the expropriation and medicalization of the female body by men, presents us with the objective means of exercising medical power. At the same time, the items of the equipment carry the characteristics of subjective femininity. In the “clinic” we see three gynecological examination chairs with unique covers, whose soft fabrics refer to the circumstances of making love. But despite the erotic connotations, the spread-out foot holders testify to the coldness of medicine, its alienation from the real, living body, and the woman’s vulnerability.

Róza El-Hassan’s emblematic action on blood donation also touches on issues of body politics, but it has a stronger social dimension. El-Hassan premiered her action R’s Dreaming About Overpopulation in Belgrade in 2001 on the occasion of the reopening of the Museum of Contemporary Art, which had been closed for three years due to the war. Beyond the layers of political meaning and moral stance, the work draws attention to the role of women in particular, that is, how women, who have empathy as their defining character trait, wish to participate in the great narrative of history. The artist presented the act of blood donation as a woman in bed, thus, through its iconography, it could be interpreted not only as a collective social act but also as a metaphor carrying symbolic meanings: it referred at the same time to the sacred connotations associated with blood donation (the blood of Christ shed for man) and feminine physical experiences (cyclically occurring bleeding and childbirth).

New media, however, seem to have become less apt to articulate feminist issues, which can be mainly explained by the fact that creative activities based on the use of technical tools, due to their objectivity and their alienating effect, are less able to represent bodily experiences and subjective perception and reception. Exceptions include the sensitive videos of Hajnal Németh and Éva Magyarósi, as well as the computer work and prints of Kriszta Nagy (Tereskova x-T). In the works of Kriszta Nagy, in which she transforms photographs, the body appears simultaneously as a fetish, a sexual object, a commodity, and as a living, transient matter. Although she is the model for her own pictures, the advertising communication of consumer culture necessitates that she always appears in a disguise: her true self is obscured by her attire, her makeup, her pose, the lighting, and even her body, toned by modern training. Ultimately, her body is always disguised by a mask, so it cannot express the subjective, inner world; what is articulated is the “social body” that plays the expected roles in a given context. In 1998, she put up a billboard on Lövölde Square in Budapest: standing in a pose that evokes lingerie advertisements, it portrays her as the ideal woman with an ideal body. In this work, which can also be categorized as street art, she is “advertising” herself as a woman artist: the ironic caption on the poster (“I am a contemporary painter”) evokes a critique of consumer culture. Kriszta Nagy’s subversive artistic language is based on the rhetoric of frivolity: it’s loud and cheeky, even when she is not criticizing the culture of communication, or the order of the signs that make up the world of pretences, rather conducting a ruthless analysis of herself. An example of that is Me and My Handsome Tom-Cat (1998), which explores the topic of ageing and change. In her latest site-specific installation, Sleeping Beauty is Dead (2019), in which, in addition to the issues of ageing and passing away, the failure of choosing a lifelong partner is put parallel to what it means for a woman to be the object of desire. Moreover, it is about how sexual and gender-based identification is related to the passage of time and the transformation in the psyche.

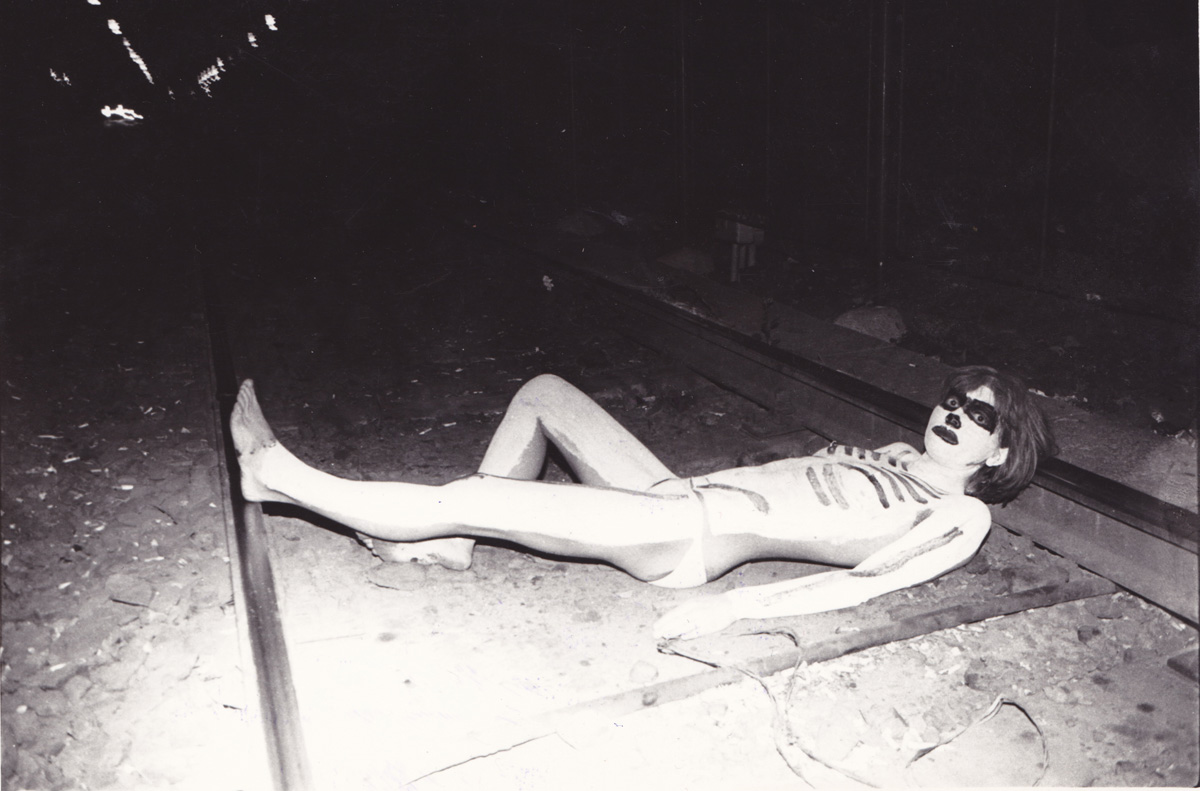

It may sound contradictory, but among the artists who use the medium of photography, the ones who most effectively articulate gender issues are those who are able reflect on gender roles by exploring the meanings behind reality with the help of essentially realistic images. A notable representative of the underground scene, Zsuzsi Ujj was one of the first in Hungary (1985-1991) to use this medium as a tool for feminist self-expression: she only photographed herself with the help of a self-timer, or sometimes instructed people to take photos of her.

Photo: MissionArt Gallery

By this time, the self-portraits of Cindy Sherman were already well-known: the artist took on a variety of roles by putting on a costume (and using the embodying power of the mask), paraphrasing both well-known female models from art history as well as her own contemporaries. Zsuzsi Ujj applied white tempera on her own body on which she painted black lines and dots: one time she “magnified” her genitals, making transparent the characteristics of her femininity; another time she drew a skeleton or a skull on herself, opening the field of interpretation toward the phenomenon of death. This series of masked-body photos portrayed feminine existence as being a ghost, a rethinking of the ‘death and the maiden’ theme from a feminist perspective.

Ágnes Éva Molnár’s photo series, entitled A Hundred Times (2015), does not show full body self-portraits, only fragments (faces, hands, legs), which, with the cursive text written on them with pen as well as the symbols placed around them (e. g. jewellery that represents the attributes on the depictions of Venus, or a skull that evokes transience), presents the issues of the appropriability of feminine identity and whether it can be allowed to be constructed by others.

(2015, giclée print, aluminium dibond, 40 x 40 cm)

The fragmented body is a central theme in feminist art, especially in painting: it is through partiality that an internally experienced, heterogeneous body that is falling apart and is intertwined with sensitivity can express itself in an authentic way. In representing her own body, the woman artist is confronted with a traditional viewpoint that reflects the male gaze. The male gaze captures the female body as one visual unit, an appropriable object obedient to the ideal of beauty.

(2016, installation)

As an opposition to this approach came the so-called ‘critical particularity’, which is exemplified in Kata Könyv’s Partially Whole (2017) series. Looking at it, our disturbance does not only stem from the horrific feeling evoked by the cut-outs, the wrong framing, or the dismemberment of the body, but also from the fact that the details, the close-ups of the skin we are presented with do not refer to a beautiful and healthy body, but to the undisguised reality of physical existence.

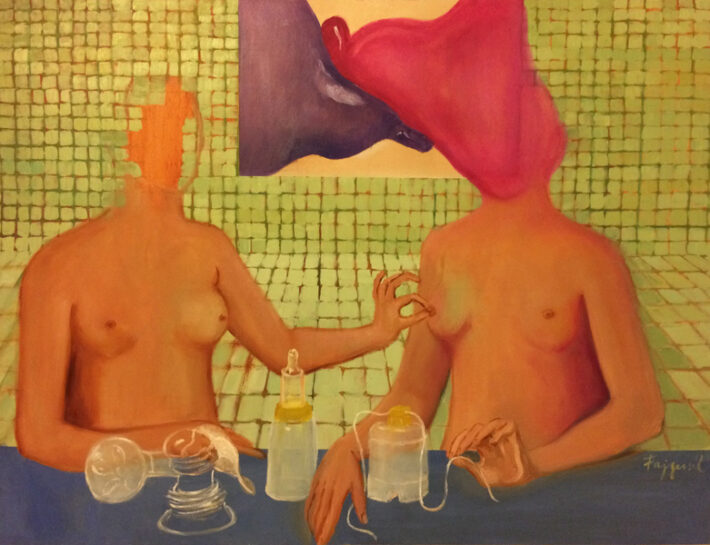

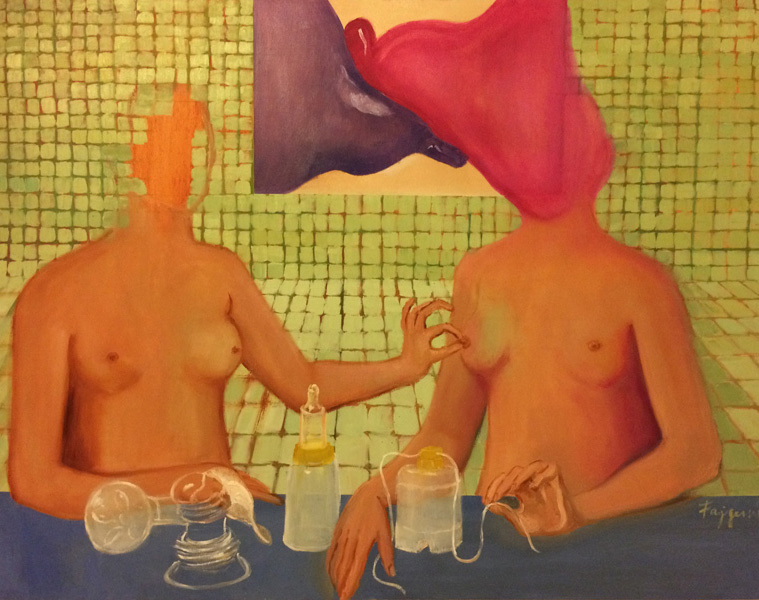

Andrea Fajgerné Dudás is the one who confronts the image of a female body removed from Greek beauty and various humanistic ideals the most radically: in her paintings and performances, she strives to make an ideal image out of her own ‘fat body’. The basis for this is a complete identification with her own body. Fajgerné does not formulate critical reflections on men’s culture, nor is she ironic, but asserts herself as woman in a naturally naive way, even if she blows up the system of expectations. Her works are all based on identification and acceptance without resignation, which can be considered a true post-feminist attitude.

(2017, oil canvas, 90 x 120 cm)

She accepted her husband’s name: the suffix ‘-né’, which originally expressed being in the possession of a man (i. e. the Hungarian version of Mrs.), does not mean subjugation for her, but the acceptance of them belonging together. In her performance, Hi’m Venus and Hi’m Grace she uses a body mask that emphasizes those physical characteristics (the flesh, the layers of fat) that are repulsive according to the beauty ideal of patriarchal culture. Dressed in a meat costume, she processes animal fat on a meat grinder, which she incorporates into a dough and bakes an edible, life-sized female body from it. Traditional feminine activities are important for her: at her eat art performances, she cooks or bakes, sometimes mixing her own bodily fluids into the food. In her self-portraits, she portrays herself naked and expresses not only her commitment to her body, but also to her social and gender roles. In her series of paintings, Married Life, both she and her husband are depicted naked, usually doing some kind of housework, in the name of equality. On the painting Rest on My Bosom (2014), the richness of the figurative motifs corresponds to the richness of the thick layer of paint – the floral pattern of the wallpaper and the floor refers to the Song of Songs. The pictorial narrative reveals the identity of the woman artist, which is not based on unity, but on the contrary, on divergence and heterogeneity. The painting paraphrases the image of the nursing Mary, well-known from medieval and renaissance art: we see the naked Virgin, whose breasts do not appear here as objects of sexual desire, but as a means of nourishment. In Fajgerné’s narrative, the mother is also a scientist who sits on top of a set of books in the midst of her daily activities to bring knowledge to her head through her womb and body. In the meantime, she can only become an artist if she uses two additional hands: a fourth to paint with, and a fifth to stir lunch with as a good wife does. So, while Fajgerné is fully able to identify with traditional gender roles, she cannot (and does not want to) portray society’s expectations without a critical voice.

(2014, oil cancas, 120 x 150 cm)

The most important aspect when presenting the various roles is always the experience of the body. Maternity becomes representable by physical experiences: in the series Annunciation (2014) we do not see the narrative of the Christian art tradition centred around the soul, but rather the processes that seemed inconceivable before the spread of feminism, and which only Frida Kahlo (one of Fajgerné’s major inspirations) could at first articulate through pictures.

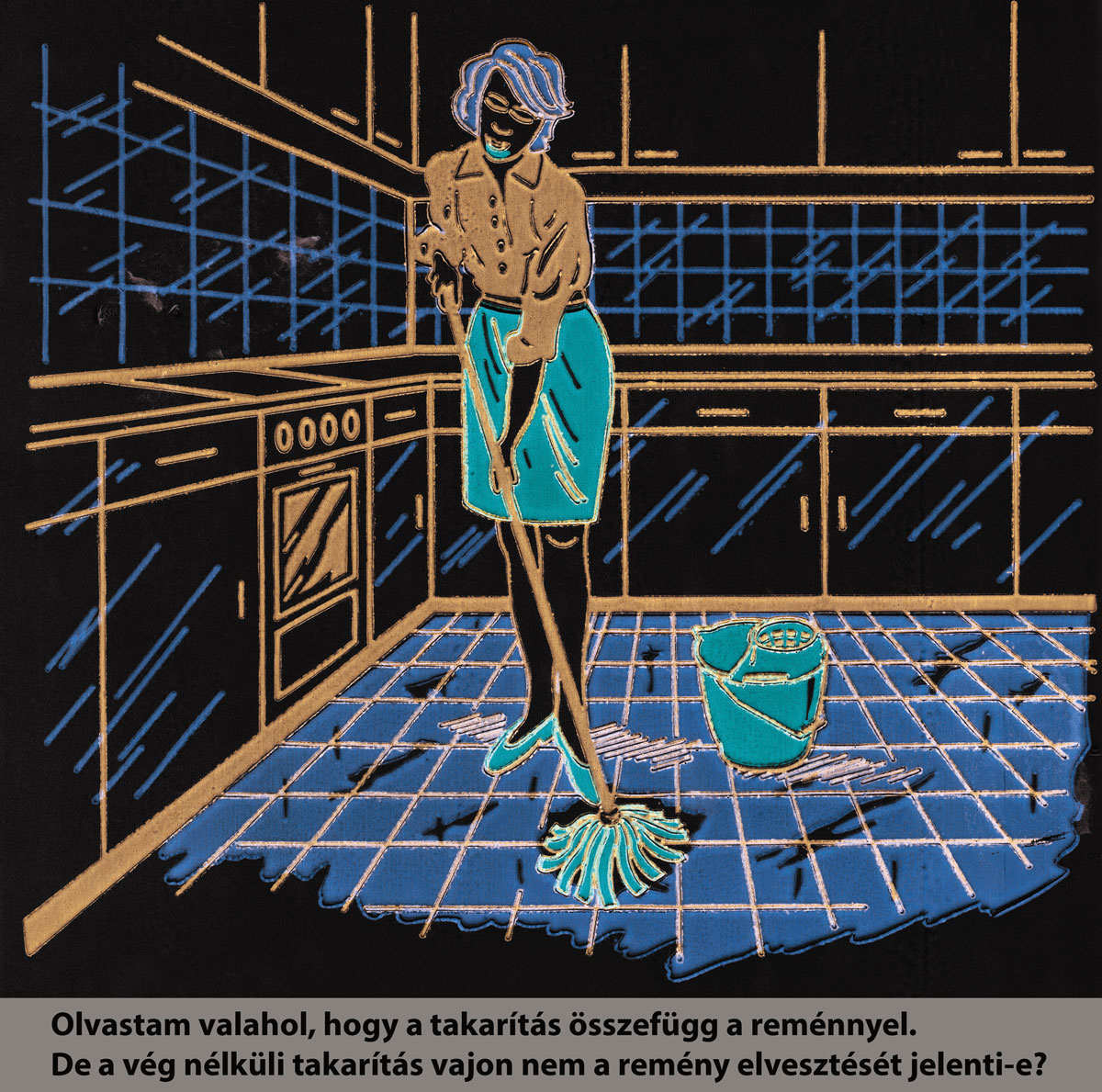

In Hungarian fine art, Ágnes Eperjesi was the first to study the gender roles directly related to motherhood, child-rearing and housework, from which she compiled exciting art narratives. In her graphic works, she uses various techniques to depict everyday utensils or food items as found objects, while she represents scenes that evoke everyday activities with pictograms or comic strips. Her topics are mostly related to women’s activities (Weekly Menu, 2000; Cooking Tips, 2002; A Sentence on Housework; 2010), focusing on feminine experiences of reality. But in addition to the issue of gender roles, she also makes statements about the meaning of everyday life in a more general way, with philosophical consistency. For example, the series Busy Hands (2000), its 12 plexiglass pieces resembling tiles, contain scenes of both men and women doing regular chores that go unnoticed, thereby pointing out the insignificance of everyday life, and how the “unreal” world around us lost its values.

(2004, lambda print, text on aluminium plate, 130 x 121 cm)

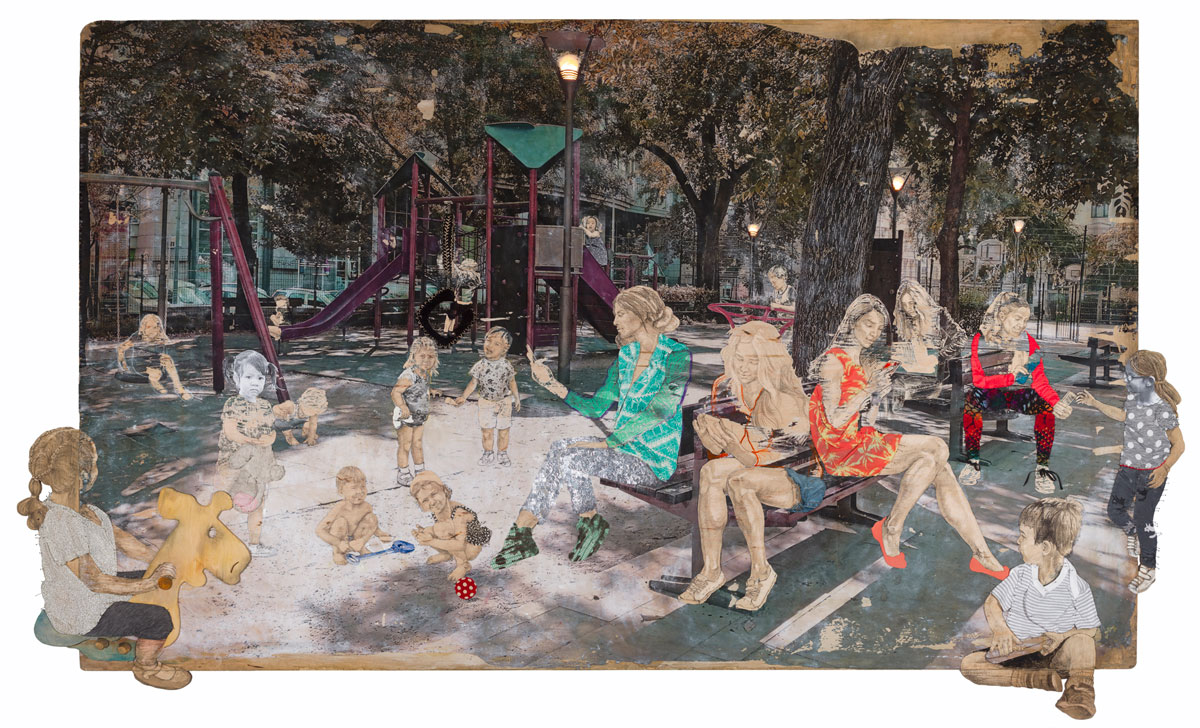

Child-rearing and women’s activities are also at the centre of Kata Gaál’s works from 2019 that are also not only about the issues of gender identity, but rather the way in which gender roles have been rewritten by changing gender stereotypes. Using old and worn drawing boards, her works, which thematize the behaviour patterns of women and children, are ready-mades and montages, sculptural objects and graphics all at the same time. The artist applied photographs, reminiscent of the faded illustrations of old magazines, onto the boards, but she also manipulated them: she inserted the facades of shops into a street scene, creating an agglomeration of references to consumer culture. Then she drew onto the redesigned cityscape and etched into the wood, and by scratching back motifs, she also created visual imprints of absence, thus bringing us to a world dominated by total oblivion of existence. These graphic narratives (We Ain’t Gonne Find Any Better; Insta Control) depict girls and women taking selfies or scrolling on their phones while shopping or looking after their children on the playground. In her other socially critical works, Gaál presents the virtual role models offered by pop culture: icons associated with gender identity that overwhelm the imagination of adults and children through various media, leaving no room for the free and conscious choice of self.

(2019, wood, textil, pin, wax, acril, graphite, led, 103 x 185 cm)

We can conclude that post-feminist artistic discourse has come a long way in the past two decades, producing countless revelatory works of art. Perhaps we can even say that during this period, the creation of a feminine identity, the expression of the characteristics of women’s lifestyle, and the creation of the signs of a feminine language were one of the most important programs in Hungarian fine arts. And the narrative that can be defined by certain highlights of artistic oeuvres also sheds light on how great this road was in its impact on philosophy and society, leading from patriarchal culture to the free acceptance and representation of femininity, or even towards a free reception of the various forms of identity. But we can also say that the path has led from the confrontational, critical practice of identity construction to the freedom of individual mythologies. Feminist women today have to fight for something else, if the struggle for self-representation can still be called a fight. In its more than 100-year history, feminism has achieved its legal and political goals, which have resulted in women being moved to a different social status – as they say, women “have achieved what they could achieve”. And this is remarkable as it has changed the world! Along with socio-political changes, our private lives have changed, as well as the forms and scope of our possibilities: in the age of individual mythologies, the self that becomes individual can now choose freely and create itself.