Attila Sirbik

The body as a certainty

„I can go to the other end of the world; I can hide in the morning under the covers, make myself as small as possible. I can even let myself melt under the sun at the beach – it will always be there. Where I am. It is here, irreparably: it is never elsewhere. My body, it’s the opposite of a utopia: that which is never under different skies. It is the absolute place, the little fragment of space where I am, literally, embodied [faire corps].” (Michel Foucault: Le corps utopique)

It would be best if the meaning and interpretation of the works in question, born in a corroded post-civilization space in which former localities are eliminated/intertwined, and may be replaced by an unprecedented heterogeneous proliferation, were as fluid and organically proliferating as the forms their creators use.

Filled with the desire to evolve, clones and mutants seem to be in terrible, continuous labour; while they cannot be born in this never-ending state, they have trust in decay because they know that all achievements and all competencies are a scam. This is the vitality that comes from decay; foreign cells that reproduce themselves. Though in the cases of Zsófia Keresztes, László Győrffy, Ágnes Verebics, Róbert Lak or István Máriás a.k.a. Horror Pista, it is not possible to decide whether the depicted, painted creatures, ceramic heads, or bodies embedded in latex are writhing at the moment of their birth or at the time of their passing; but it is also possible that the two are the same in terms of creation. A well-rounded team of geneticists and doctors lean over the pulsating paradox and stick their heads together; they are far from going unnoticed, and they are not even aware of the consequences. But faith is the guarantee of the things we hope for, the proof of things that cannot be seen, as well as the fear beyond matter, where there is no freedom, only an impassable border; that is where the body develops. More important than this border-experience, however, is the openness that comes from the re-created sacredness and the waves of doubt, which cause the surface of the flesh to dry, crack and then split open as the conventional categories of intellect begin to collapse. The lingering disintegration, which is the very nature of the body, is swallowed up by the aura of miasmic vapour that leaks through the skin of Bataille and then vibrates in the air. And it is now a radical and irreversible decision to utilize dysfunction and chaos in the representation of the hybrid aesthetics of decomposition. The starting point is hybridization, and deterioration is fresh blood for the vampirism of understanding. On the other hand, the border is just what is needed, since it can be crossed over and over again: these border violations are a symbolic game in the space designated by art which lacks the naive idealism of changing the world. An electrifying gesture, the ecstasy of instinct, the evoked horror, the deconstruction composed of rusted metal and scrap wood, the monad-like closing of the Western mind, the detonation of a subject trapped in the dialectic language.

By distorting our realistic image of the body and shifting it toward a magically fictitious false reality, these artists (as well as their creatures) also suggest to us that mocking a humanistic body image that can be described as “realistic” generates a dangerous, subversive laugh in them.

Hybrid aesthetics, biomorph paradise

Győrffy is terrified of the dimension beyond materiality. Although language itself has an immaterial dimension, it is brought to life by a non-eternal nervous system: our metaphors for describing the world beyond matter are beautiful, but do not help with the fact that everyone dies. His works basically reflect the experience of being embodied (i. e. being deposited in a body), without the traditional idealism of art, which was well established in Bataille’s base materialism by abolishing the hierarchy of above and below: bronze as a medium inherently has no greater aesthetic value than, say, snot.

According to Győrffy himself, he always found the human body to be wrecked and distorted rather than ideal; he became interested in the artistic methods of deforming the human body very early on, well before college or even in high school. For him, this kind of destruction is not some sort of degradation process, rather an escape route from an exclusionary beauty ideal that allows the proliferation of different, hybrid bodies.

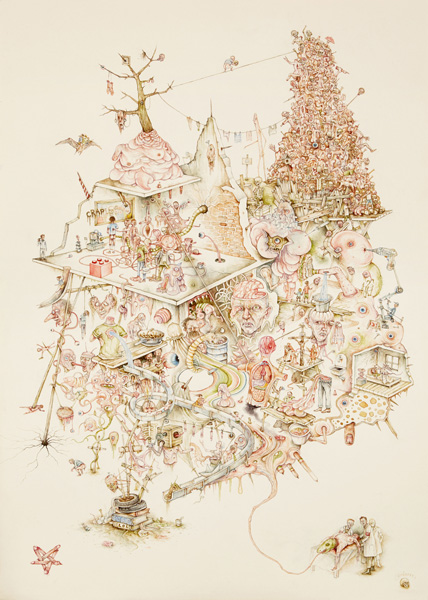

The formlessness that often wobbles between representation and abstraction is part of a kind of hybrid aesthetic. Crossing the boundaries between dichotomies also belongs to the essence of hybridity. For example, the episodes of the creation story depicted on Győrffy’s apocalyptic etchings, or the pieces of his painting series The Black Rainbow/Inauguration of the Worm (2015) are actually interchangeable, since in one of the images 9/11 happened millions of years ago: they show a transhistorical dramaturgy that is not centred around humans. In this sense, these beings, or rather, mutant organisms only resemble the human face or shape in awkward traces, making their position purely parodistic. Győrffy’s Miasma Project, on the other hand, is a slightly different approach than hybridity. Here, his figures are no longer hybrid beings. In their case, one thing becomes irreversible: not the realization of rearrangement, but the fact of decay, where the artist deals with the vitality that comes from decomposition along his typical post-apocalyptic anthropology, based on horror traditions. According to Bataille, “Blindfolded, we refuse to see that only death guarantees the fresh upsurging without which life would be blind. We refuse to see that life is the trap set for the balanced order, that life is nothing but instability and disequilibrium.” In his sour revelation, Győrffy is interested in rewriting childhood visual experiences as well as the study of dead or zombified genres of fine art – his works blend private images and official representation through a variety of media.

Győrffy has always considered bare fiction more important than stripped down reality, which is even more exciting if there is a little clothing left on it, even if is in shreds; this torn-up costume is an accurate representation of the position and role of “experiencing reality” in his works. For him, the self in itself is a conceptual construct; together with appropriated quotes and references, quasi-personal fragments are embedded in the fabric of a rhizomatically organized reference network from which it is impossible to unravel the origin of motifs. Győrffy’s latest work, Exquisite Corpse IV (In his dream Grünewald finds the index finger of Imre Bartók in the shadow of endorphin-reefs, 2019) not only recalls the title and the motifs of Imre Bartók’s prose, especially the universe of Jericho Under Construction, but its whole structure by creating a new hybrid tissue through demolition. Regarding the anatomy of cognition, Győrffy is happy to share the box metaphor with Bartók: “If writing itself is like boxing, then a book is nothing more than a magic box with matryoshka-like structure, which contains more and more boxes; however, the ultimate secret, the metaphysical core, similarly to an excavation, is unattainable, since each box only contains another box ad infinitum.”

The world of Lak, which is a kind of biomorphic paradise, the paradise of (walking through) hell, is also somewhat in tune with the universe of Győrffy. There is a distressing continuity in the way Lak constantly returns to the same place and starts over; many of his pictures seem to be the same, a kind of mantra-like repetition as a conscious form of self-emptying. It is like a local, accelerated attempt of an incarnation of a single soul in the same body, so that it changes, stretches, spreads, or shrinks just slightly, as if something had just sucked the life out of it; continuous dying and resurrection. It is not an intermediate state, neither the desire for inhibiting the life trapped between the nothing/something before and after life, but a continuous copy-making, a visual condensation of the philosophical categories of ‘same’ and ‘nothing’. The painted creatures of Lak carry dimensions beyond matter. Dysfunctionality is supposedly unsettling because it is unacceptable for a person not to represent something truly valuable. The useless is worthless. I think there is no real hybridity in Lak’s works. Of course, it is always worthwhile to make assumptions, and Lak’s pieces would like to suggest that there is a chance that something may re-form, but the realization of that formation is something that is constantly lacking. Religious coexistence, sado-masochism, the hiding Elephant Man, who is emerging from Lynch’s armpit as an embalmed bovine embryo, who then suddenly gets excited to book a trip and becomes the eighth passenger on the space shuttle of Giger, the opiate-addicted Swiss painter, to break out of Kane’s chest at lunchtime and wink at Bobby Peru, who will surely fuck Lula one day, but not today, because he has to hurry. Those that walk through, spend time, pop up, get copied into each other in these spaces are not morally weak, but rather wild creatures beyond any kind of morality, alien to the pain of existence, ready to challenge the logic of perception and cut Deleuze’s throat, and who would love to direct the blood splashing from the great philosopher’s artery directly to Bacon’s face. Do the figures in the paintings wear masks, or are they the inspirations for well-executed masks? Is this a clothed or a naked “reality”? Does this matter at all, or are there continuous distortions, and as soon as you ask a question, it cancels itself out immediately?

So, is it Kane, who has no facial expressions due to the mask built onto his face, or is it the pitiful figure of Merrick that emerges from Lynch’s armpit? What is more important is to look behind the distorted exterior. While ever-changing creatures cleverly avoid clichés, pathos, and kitsch, violence appears as a clinically pure abstraction on canvases depicting these softened figures; or, if not on a canvas, then an aluminium tray or the heavy door of a Socialist cabinet made of chipboard. Lak’s works primarily depict enclosed spaces with biomorphic, always human-like figures sitting, standing or lying in twisted poses. These figures usually have a naturally coloured flesh, but are often bloody, have a smell of decay, and they can take on all colours of the spectrum. It is as if there is some kind of coincidence- or error-provoking awareness in the spaces around these distorted figures, which always pushes the creative process in a completely different direction from the way it started. Although all of them are obviously painted with a brush or a spray gun, it is characteristic of Lak’s portraits and human figures to bear errors typical of analogue photographs and traditional films, such as the oval distortions appearing after developing the film, or scratches and other disruptions. For a painting, this means that its texture is enriched by adding a new spatial layer with each new layer of paint. The original, relatively realistic figure is often covered with so many additional layers that it is almost or completely unrecognizable. So there is no hesitation and correction and transparency, but a highly expressive form of expression. Then, as if they were suddenly put in Poe’s inquisition chamber. The victory of the soul over the flesh. This flesh does not want to please, but latch onto your heart as an octopus and feed on it. This may be our only chance if we become like these post-apocalyptic creatures, and wait for a definitive, inevitable, and irreversible end in a completely emptied, windowless room; where the end is a perpetual repetition of a game that is always the same. The figures of Lak in this eternal repetition are perhaps the last human beings to evoke centuries-old traditions of individuality with their torso, whereas their identities are merely indicated by truncated and unstoppably decaying and fraying bodies. The people in Bresson’s (and sometimes Fassbinder’s) spaces can suffer like this. Lak reverses the constructivist El Lissitzky’s statement, “We reject space as the painted coffin for our living bodies.” For Lak, even the landscape, the green of the meadow, is merely a pathetic illusion of freedom trapped within the coordinates of perspective.

The objects of Keresztes are subjects without identity in a post-apocalyptic dimension; beings who cyclically devour and recreate themselves, but in their case perfection is not an issue or a goal; that is not how they operate. Rather, they exist in a kind of self-inducing process within a monotonous cycle, in which something is added to a creature in a certain moment, and some sort of “cell proliferation” begins; or in the other instant the thing turns back into itself, taking away from what it has already incorporated, and is thus forming. These effects are neither positive nor negative, they just happen and that’s it. Some of Keresztes’s creatures resign to their lonely fate, while some divide and create a company for themselves, thus, the absence is mutated to completeness.

Photo: Tomáš Souček

The false obsession with perfection can be called mutation in this dimension, which is no longer aimed at perfection, but at survival by adaptation. Borders are blurred between opposing parties, who are enemies and allies at the same time. Their caring touches leave their mark on the other as well as their destructive attacks. They adapt, and strive for equalization. They “snack” on one another, take on the other’s experience, then knead it, shape it, and offer it to their partner, or to themselves. This kind of “self-cannibalism” is reflected in the fact that, for example, one shape is repeated several times on one body. For example, on My Dearest Enemy or The Totem of Hidden Profiles, repetitive shapes refer to paired organs or body parts, as if they were the embodiment of Siamese twins or avatars. Keresztes’s objects are generally associated with the fluidity of the net in the sense that liquids, unlike solids, cannot retain their shape; neither the space is fixed, nor the time is bound. This may seem contradictory because of the use of materials, and of course, when we look at these objects, we see solid, statue-like figures. Even so, their shapes resemble some kind of flowing bodies, which give the illusion that they can take on different shapes at any time, and that they have many forms hidden in them.

Domestified horror and the temptation of reality – art capsules against sociopolitical amnesia

In the dimensions of horror, there is always a kind of unbridled freedom, an imaginative outgrowth of instinctive curiosity, and the liberating power of fiction. Where the fictional reality of a fictional object is placed next to the reality of a real object, the function of the imagination is enhanced. In the case of István Máriás a.k.a. Horror Pista, the use of this space is conscious in some cases; however, in some of his works, especially in the meticulous, carefully crafted space of mini-installations, it seems that he repeatedly goes beyond intentionality, giving a chance to instinctive expression to present itself. In such cases, he crosses the border within which we still have actual grips to politics and public life, where the socio-horror is born. In the case of these border-crossing works, however, the viewer’s intellect can roam much more freely: these works no longer trigger only intellectual but also emotional reactions.

Some of Horror Pista’s works are playing with the temptation of a realistic state of being, so these pieces are less fictional, but they are really exciting because their life dimensions start and return to reality: they create a kind of realistic horror, domesticate the dimensions of horror and make it familiar to us by not creating, but rather showcasing our little home-made everyday horrors. But let’s take a look at exactly what and which emotions are played off by Horror’s aesthetic range. First and foremost, there is the group of well-known fairy tale topoi that have fossilized into the deep layers of the unconscious, and into which Horror discreetly lowers, sinks, submerges his drill head, while also stirring up experiences based on prejudices, which regard some of our senses (smell, taste, touch) as inferior or base. But let’s consider another central motif of his: frustration. What can you do with the anthropological magic tricks of the cult of the body that emerges from the mirror-smooth waters of the advertising world, which is deeply embedded in capitalism, if we associate the body with frustration, mutation, ugliness, insanity? In the light of history, reality often carries the most absurd situations. Through his own filter, Horror passes on actual past experiences, be they personal or collective, to sublimate them into works of art in his workshop, his creative space.

In these works, he also expresses social criticism, often imbued with thick irony and, occasionally, a hefty dose of cynicism. He makes visual medicine: art capsules against sociopolitical amnesia. In many of his works, not only fiction but rather the temptation of the realistic state of existence can be discovered, which creates the magical, suggestive power of his visual language. In the details of some of Horror’s works, as well as in these details’ context, the disgusting and the sublime meet with a sense of balance; there are also cases when the balance is tilted for some reason, but only rarely. Thus, by injecting the sublime and the disgusting into each other (I would by no means say ‘squashing them together’, because in most of his works there is no sign of aggression, rather careful deliberation is what dominates), it creates in us a kind of visceral, sensual and at the same time reflective attitude. “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” Why this quote? It is right here, in this act of absence by the artist, precisely in the gesture of prudence, that we are shown the paralysis embedded in the terror of action, the power of inactivity born from sophisticated forms of fear-mongering. These dimensions are illustrated, for example, in those of Horror’s works that embed the relationship between society and the individual. In this world of Horror Pista, this system of relations is immensely complicated and complex, for it infiltrates the world of apocalypse and science fiction beyond duplicity, perversion and hypocrisy. In case everyday horrors were not enough for you, or if you were to get rid of it, if you were ready to make peace with the fact that anyone’s head could fall off at any time, or that whoever is embracing you is just a skeleton, you cannot escape either because you are hunted down by a strange creature or punished by your dreaded teacher. But these are all just projections. Which are nothing but the shadow of our most hidden inner fears. A grossly light egotrip. Or something completely different.

Verebics, though of varying intensity, has always been interested in the human body as a depicted object, as a motif with content and layers of meaning. The body sometimes appears uncovered and sometimes in symbolic clothing, often pushing the limit of extremity. She is attracted to portrayals of peculiar, often deformed, strange-looking people as well as animals, or extreme figures produced by distorted Western (or even Eastern) cultures, and those affected by genetic disorders. She sees the Self as polycentric, multi-layered, unstable and historically situational, a product of continuous differentiations and multiple identifications. Therefore, she does not perceive verbal or cultural exchange taking place between bound individuals, rather between malleable, transformable subjects. In the constant struggle with hegemony and resistance, every form of cultural intervention changes both participants.

The works of Verebics suggest that the body is the only certainty in general uncertainty. What are we seeing? Body manipulation, visual-metaphorical distortions of an actual image of the body, the illicit body, gesture essences, i. e. the visually amplified body-signal as a compression of the symbolic space. Verebics creates a world that refers to more than just reality: to the conceivable thought which is forced, or, in a better case, which is besieging the surface of subjectivity.

When viewing Verebics’s images of bodies, it is not at all certain that we see what we are looking at. Her vaguely false representations of animals tend to refer to human behaviours that are considered deviant in some respects, as well as extreme and subcultural fashions. For example, when looking at a goose wearing a latex dress or a rooster decked out in leather, our mind almost immediately jumps to sadism and masochism, or the aggressiveness often mistakenly associated with punk (sub)culture. The artist uses a rather peculiar and interesting approach and creative representation, with which she seems to want to create a presence for the “other world” in our world, which (however strange it may sound) is the essential presence of absence in the foreseeable, perceptible and perceived presence. Ultimately, there is no hiding, no hidden meaning here, everything is unpacked; we just don’t see what we are looking at, that’s all. Among other things, this is the genius of Verebics. We are getting even closer to her subjects, the human bodies, by the fact that they are not even present this time.

Using various techniques, the overlapping of dimensions for displaying the body or physicality is what Verebics’s pieces are mostly born from. While some of her works carry the marks of horror aesthetics, incorporating its ugly, scary, provocative characteristics, other projects, such as Hairy Gang, at first glance, reveal a sort of over-aestheticized world. This series of female nudes depicted with incredibly lush hair that also takes us into the world of fashion, has an amazingly powerful atmosphere. It’s as if we were looking at trendy women on the catwalk in the latest collection of hairy outfits. However, despite the fact that we are “facing” shapely, fit female bodies with rich hair hanging almost to the ground, many possible interpretations and, at the same time, misinterpretations can occur. Who are these women? Are they prehistoric women waiting for a marrowbone at the entrance of the cave? Are they androgynous beings, well-made wax dolls, sorceresses, taxidermied women who have been mummified for years until their hair reaches their ankles, dominatrices blessed with power in their hair, or are they the cursed results of atavistic genetics? Perhaps a sort of essential presence of all this is condensed into these creations, or rather, creatures, beautiful hair monsters created from human beings. Though not as vigorously and clearly as in Verebics’s many other works, the beautifully dreadful presence of horror is there lurking and fluorescing in them. It is an attractive and repulsive, freezing duality. Indirect, subtly hidden, suggestive horror. Verebics incorporates into the Hairy Gang series a moment of intense detachment from reality by resurrecting indolence in her models, by which they cease to be models, and become bearers of concepts hidden in indolence; faceless beings who carry within themselves the duality of existence and appearance. But this duality does not exist between the body and an assumed role (this time conferred on the models by the artist), but rather within the body itself. After all, our image of a human as a model ceases to exist; the artist eliminates the desire in her models to represent themselves.

In Verebics’s works, representation moves in the direction of the representation of the objectified body, and a specific segment of it, which in a sense takes over the role of everything, eventually replacing the body carrying it and referring to a distant, flawed, genetically defective body. For Verebics, it is inevitably important to grasp and show the essence of “beingness” through the depicted figures. It is no coincidence that we are talking about figures, since it is crucial for the artist to show the absent body that she perceives in her models, the desire for creation making her grasp it. In this case we are dealing with a special situation, since instead of paintings we are talking about photos depicting figures of flesh and blood (how many times do we have to forget this while looking at them?).

These behavior-less women (whose physical endowments are almost entirely obscured by “hair power”), elevated into works of art, blur those boundaries and mould those positions of the viewer, legitimized by society and mass culture, that would instantly transport us to the sensual dimension of sexuality. Instead, the shapes that are obscured under or rather behind these waterfalls of hair, develop into a sort of as if-identity in the gap between the deeply personal and the impersonal, not necessarily losing, but transcending their feminine identity. A strange mixture of homeliness and alienation, mysteriousness, and a kind of eeriness is present in this work all at the same time. Hairy Gang is a kind of mixture that blurs the boundaries, the demarcation line between bodily existence and computer manipulation. At the same time, the irony of this gesture cannot be ignored, since Verebics does not use the clone stamp tool to adhere to the unrealistic standards of fashion photography by endlessly chiseling the images, but only for manipulation and to enhance the mound of hair. In this way, the atmosphere of fashion mixes with ancient spiritual features and a kind of degeneration, creating the feeling of “I desire it, but I would not let it into my home”.